WHAT IS HYPERMOBILITY ?

Joint hypermobility refers to joints that possess greater than average range of motion, and when not well stabilized by appropriate active stabilization, more lax, or loose, and therefore move farther and/or are less stable than average. Generalized joint hypermobility is is caused by genetic variants that result in a congenitally less stiff type of connective tissue, making joint capsules, ligaments, tendons and other structures of the body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, that contain collagen less resistant to stretching. Due to the fact that most structures in the body contain collagen hypermobility actually affects the body as a whole, and not just the musculoskeletal system. Hypermobility exists on a broad spectrum, and when joint hypermobility leads to, or contributes to, pain and dysfunction it is referred to as hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) or, if certain diagnostic criteria are met, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS). EDS is estimated to affect 1/5000 individuals. Generalized joint hypermobility is a genetic trait, in other words inherited, and in the variant called hypermobile EDS possibly the result of several different gene variants, and therefore varies quite a bit in terms of its manifestation. A paper published in 2014 suggests that hypermobility indeed exists on a spectrum and consists of one single entity with differences only in the degree of expression. Women are at greater risk of symptoms of hypermobility, and tend to experience a greater degree of early osteoarthritis, presumably due to sex hormone differences and differences in muscle mass between women and men.

All individuals on the hypermobility spectrum are -- to varying degrees -- at an increased risk of various injuries over time, and can greatly benefit from an increased understanding of their body and the individualized approach to keeping it healthy that is required. There is also great variation between individuals in terms of the location and type of symptoms.

Individuals on the hypermobility spectrum are at increased risk of various injuries over time and can greatly from an increased understanding of their bodies and the individualized attention that they require.

The bodies of hypermobile individuals benefit from skilled and specific care, in which physical therapy plays a very important role. The joints of individuals with hypermobile soft tissues are inherently less stable and require an increased focus on protective stabilization from muscles. Proprioception -- the sense of the body's position and movement in space --is decreased in hypermobile individuals, and increased work on balance and coordination is necessary in order to avoid both acute and gradual injuries. The various pain complaints and musculoskeletal injuries that occur with hypermobility can best be understood and managed when the common, underlying cause, the extensible and weaker connective tissue, is kept in mind.

The hypermobility spectrum is also frequently correlated with a great number of non-musculoskeletal manifestations, most of which probably have as their common denominator the increased extensibility or weakness of the connective tissue and subsequent changes in the function of the autonomic nervous system. Understanding the common denominator can help ease psychological distress and help manage these comorbidities more effectively.

Hypermobility is underdiagnosed and all too often not comprehensively managed. It is insufficiently emphasized in the education of healthcare professionals, and therefore not always recognized as such. This may lead to inappropriate care of the hypermobile individual, as the interventions best suited for non-hypermobile individuals may not be the most appropriate ones for people with EDS and HSD.

Often, even hypermobile individuals themselves don't realize the existence, extent and repercussions of their hypermobility. Even individuals with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome may suffer from various complaints associated with the condition for a decade or longer before being diagnosed with EDS.

Individuals often do not even themselves recognize their flexibility as hypermobility, and therefore may not realize that the various non-

musculoskeletal manifestations of their connective tissue composition are also a consequence of it.

a

Over time, and if not protected by sufficient muscle strength, coordination, proper ergonomics and proper dosage of exercise (through avoiding both under-or overtraining) hypermobile joints are at risk for both acute and gradual injuries, and this may over time result in arthritic joints, painfully tight and overworked muscles, chronic spinal problems etc. However, it is important to understand that the pain associated with, and caused by, hypermobility initially is not primarily caused by injury or damage, or primary arthritis, but by sprains, strain and overload of primary mover muscles due to poor control of stabilizing muscles and joints, and is therefore it is usually benign and self-limiting when managed well and in a timely manner, early in its course. In the long run, if not managed appropriately, joints and associated structures may suffer more permanent damage. In all cases, it is helpful to understand that pain in hypermobility disorders is not spontaneous and unavoidable, but arises due to poor functioning which can, and should, be addressed, through physical therapy and other means.

Understanding the specific needs of hypermobile bodies is of great importance, and following an exercise program specifically designed to enhance stability before strength can go a long way towards preventing potential problems. Hypermobility is a trait, not an illness. Only when it contributes to pain and dysfunction is it called a syndrome.

The hypermobile individual needs to realize and accept that a sustained effort is required to improve

their situation. The negative changes didn't happen overnight, and --depending greatly on the current

degree of de-conditioning-- improvements in the body will also take time. The body changes on its own

schedule, and muscle, connective tissue and the nervous system that governs our movement change

according to their own time table. The good news is that with the right information and proper care, a

hypermobile body can thrive, existing impairments can be managed, and future problems prevented.

The HSD/ EDS patient should in most cases be prepared to engage in the rehabilitation for several

months, in some cases much longer, and this includes regular "homework": therapeutic exercise, ergonomic improvements, the use of assistive devices etc. This work can be a lot of fun, and patients find

seeing the changes In their health and function very rewarding.

What does hypermobility look and feel like?

As a child, the hypermobile individual may, in addition to being very flexible, walk later than average, fatigue more easily, have trouble gripping pens in a conventional way, appear clumsy and suffer from non-musculoskeletal conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, anxiety, dental problems etc.

Hypermobile Individuals may often display a somewhat "collapsed" posture with winging of the shoulder blades, hyperextended knees, and prefer to not stay in one static position too long. Many, especially if they aren't physically active and possess good strength, may start to experience a variety of musculoskeletal pains, subluxations of joints etc. Despite their general flexibility, they may experience their muscles as "tight", due to pain, static muscle contraction caused by loss off deep stabilization, faulty end-range postures, decreased stiffness of the tendons contributing to a partial loss of muscle relaxation, and the added load on muscles supporting the body without the help of sufficient ligamentous stability.

Over time, poorly protected joints are at greater than average risk of osteoarthritis, and actual stiffness may set it.

A vicious cycle of pain, poor sleep, anxiety, fear of movement and exercise, leading to increased weakness and instability, leading to more pain is common. This cycle can fortunately be broken with expert guidance, gradual progression and perseverance.

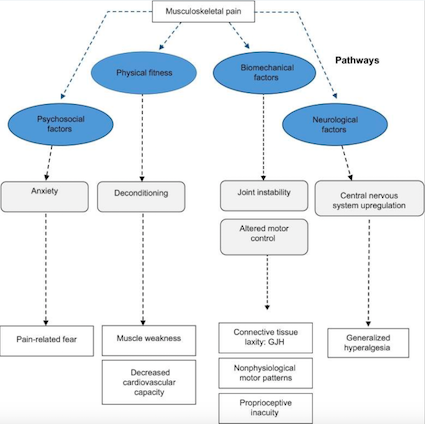

A model (Sheper et al, 2015) of various factors contributing to pain in hypermobility

|

Musculoskeletal manifestations common in hypermobility The hypermobility varies in both location and extent from person to person, so that no two hypermobile people are alike and share all the symptoms. One person's hands may be more hypermobile, while and another person notices more symptoms in the spine or lower extremities. Common musculoskeletal manifestations of hypermobility include:

With the gradually increasing pain and fear of activities that might cause pain, general deconditioning and weakness and increasing sensitization to pain may occur, leaving the hypermobile joints ever more vulnerable. On the other hand, pushing ahead with activities that benefit individuals with normal connective tissue may lead to accumulating injuries and degenerative changes that ultimately prevent desired levels of physical activity. As EDS/HSD run in families, a certain degree of flexibility may seem normal, and consequently the hypermobile person often does not realize the extent of their hypermobility until symptoms start to accumulate. Recognizing joint hypermobility early and treating the body preventatively is a superior strategy. Stabilizing the body "from the inside out" and creating helpful, protective habits is much more effective in the long run than simply reacting to pain as it occurs. Early intervention also helps prevent the slide into a self-perpetuating cycle of weakness and pain, where one leads to more of the other. Early intervention also helps maintain general conditioning and fight the fatigue that otherwise often accompanies EDS/HSD. Hypermobile parents should be on the lookout for symptoms of hypermobility in their children, as there is at least a 50% chance that children will inherit such traits. Little children that fatigue easily, "growing pains", difficulty holding a pen with a conventional grip, hand pain, problems with handwriting, neck pain, anxiety etc can all be signs of joint hypermobility. Please note, however, that children in general are "looser" than adults, and a small amount of hypermobility in a young child does therefore not necessarily mean that the child will be hypermobile through life. |

Non-musculoskeletal manifestations of hypermobility The non-musculoskeletal manifestations of hypermobility are many and vary from person to person. An incomplete list of he comorbidities that may occur, to varying degrees, includes:

|

The importance of skilled physical therapy for the prevention and treatment of musculoskeletal injuries and pain in hypermobility disorders cannot be overstated. The decreased strength and firmness of the connective tissue is a hereditary, intrinsic characteristic that cannot be changed (although we all do become less stretchy as we grow older), and therefore the hypermobile person must instead compensate through stability, strength and increased focus on proprioception and balance in order to both prevent acute injuries and gradual degeneration through micro-injuries, small injuries that occur every day, and have a cumulative effect, causing gradually increasing pain and dysfunction. Hypermobile soft tissues such as ligaments, joint capsules and tendons offer less resistance to stretching and movement, leaving joints poorly protected. Pain can result from subsequent joint injuries, from increased load on fragile ligaments, from weak muscles that are chronically overworked due to the underlying instability, from the poor balance and coordination often seen in hypermobility as well as dysfunctional movement patterns and insufficient movement resulting from pain and kinesiophobia (fear of, and avoidance of, movement). Forms of exercise and sport that are recommended for the general population may not be appropriate for hypermobile persons. The person with a less severe form of hypermobility may well become able to tolerate most forms of physical activity very well, but only after properly training the body to be stable and well coordinated. Diving in head first into the desired sport or activity without the needed preparation may be a recipe for injuries and pain. The fundamental role of stabilization Hypermobile individuals benefit from a strong focus on activating the stabilizing muscles of the body. These muscles do not create movement, but instead work to keep joints stable. They are located deep in the body, close to joints, and may easily-- due to pain, inactivity, passive postural habits etc--become weak and underactive, leaving joints poorly protected. Hypermobility also predisposes the individual to decreased activation of stabilizing muscles, as these muscles rely on information from the various sense organs located in ligaments, tendons and muscles, the very tissues that due to their extensibility contribute insufficiently to this information flow. When supported through appropriate types and sequencing of exercise most hypermobile patients can take powerful steps to protect their bodies, help them function better. The right interventions can help them improve tremendously and even thrive. The many hypermobile dancers, athletes and circus performers are an encouraging examples of the empowered, strong face of hypermobility.

Diagnosing hypermobility

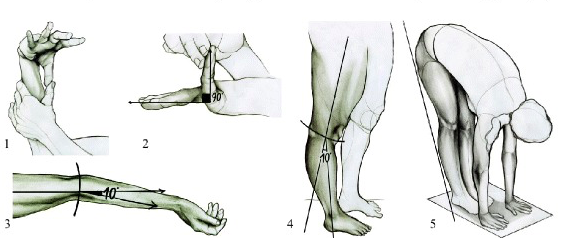

The Beighton score is used to identify and diagnose hypermobility. Using the Beighton Score, one point is assigned for the ability, now (or in the past) to accomplish each of the following movements. Can you, or could you ever

The criteria for hypermobility are as follows: >=6/9 Children and adolescents >=5/9 Pubertal men and women to age 50 >=4/9 Men and women > the age of 50 The diagnostic criteria for hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, revised in 2017, can be found here. If you think you meet the criteria for hEDS you should seek a formal diagnosis from a qualified healthcare provider and seek genetic testing to rule out other forms of EDS, such as vascular EDS, or vEDS. The Beighton score is, admittedly, a very imperfect tool, as it selectively measures hypermobility in a few joints only. Since the degree of hypermobility in specific joints varies from person to person, so that one individual may, for example, display more hypermobility in the trunk and another in the hands, the Beighton score may fail to capture the degree of hypermobility in many individuals. |

Resources:

Medical Professionals familiar with HSD/EDS in the Chicagoland area

Hypermobile EDS 2017 Diagnostic Criteria

BLOG POSTS WITH SPECIAL RELEVANCE TO HSD/hEDS

Common pitfalls in physical therapy

The Reationship Between Pain and Safety in Hypermobile Individuals

Hypermobile? Five Principles to Make Physical Therapy Work For You (Published on www.hypermobilitymd.com )

How to Get The Most Out of Your Physical Therapy For Hypermobility

Spinal stability - what it is, why you want it and how to get it

Helpful lifestyle choices for the hypermobile

Balance, stability and coordination - the secret superpowers that keep us safe, strong and upright

When pain doesn't mean stop

Overcoming chronic pain -what have nerves got to do with it

OVERVIEWS OF HYPERMOBILITY SPECTRUM DISORDERS / EHLERS-DANLOS SYNDROME

https://ehlers-danlos.com/wp-content/uploads/EOOD-2016.pdf

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Hypermobility_Syndrome

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/joint-hypermobility-syndrome#H26926682

https://www.mountsinai.on.ca/care/pain_management/lecture-series/ehlers-danlos-syndrome-presentation

https://www.inmotiontherapymontrose.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/hypermobilityfinal-AK.pdf

HYPERMOBILITY AND EXERCISE

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25489549/ How tendons and muscles thicken and improve with resistance training

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20576846/ Why stretchier tendons create less muscle strength/force

https://breakingmuscle.com/amp/fitness/training-with-hypermobility

SUPPORT ORGANIZATIONS AND ADVOCACY

https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/

https://www.ehlers-danlos.org

https://www.hypermobilityconnect.com

GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS:

https://ehlers-danlos.com/2014-physicians-conference/Collins.pdf

https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/pdf/2017-FINAL-AJMG-PDFs/Fikree_et_al-2017-American_Journal_of_Medical_Genetics_Part_C-_Seminars_in_Medical_Genetics.pdf

HYPERMOBILITY AND NUTRITION

https://nutritionaltherapy.com/hypermobility-and-functional-health-a-concise-introduction/

http://www.eds-nyc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/EDSnutritionalSupplements.pdf

PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS, ANXIETY AND PSYCHOSOMATIC DISORDERS:

www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/161887/anxiety-disorders/anxiety-and-joint-hypermobility-unexpected-association

www.scientificamerican.com/article/people-who-are-double-jointed-are-more-likely-to-be-anxious/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3365276/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajmg.c.31544

HYPERMOBILITY AND CHRONIC PAIN

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548768/

https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(17)30220-6/pdf

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2013/580460/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255738020_Evaluation_of_Kinesiophobia_and_Its_Correlations_with_Pain_and_Fatigue_in_Joint_Hypermobility_SyndromeEhlers-Danlos_Syndrome_Hypermobility_Type

https://ehlers-danlos.com/wp-content/uploads/EOOD-2016.pdf

HYPERMOBILITY AND SLEEP

https://youtu.be/xa208m4DuPw

HYPERMOBILITY AND DYSAUTONOMIA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6pmv_Pt2ulY

HYPERMOBILITY IN DANCERS

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iadms.org/resource/resmgr/Public/Bull_2-1_pp5-8_McCormack.pdf

PERIOPERATIVE CARE IN EDS

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=97524

THE IMPORTANCE OF MAGNESIUM IN HYPERMOBILITY

https://ehlers-danlos.com/wp-content/uploads/Collins-Magnesium-and-EDS.pdf