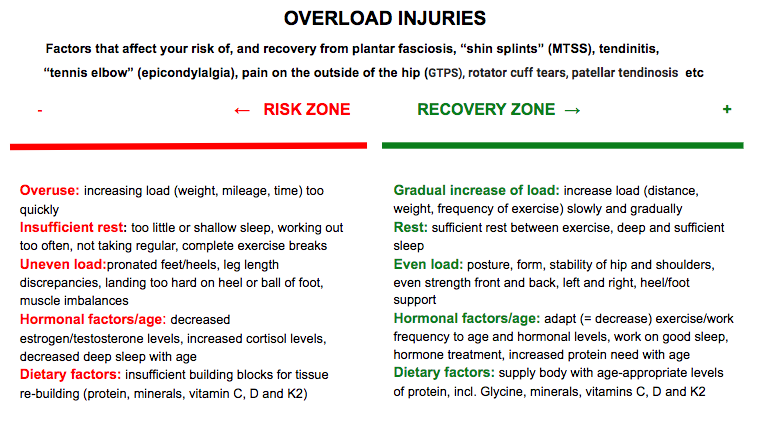

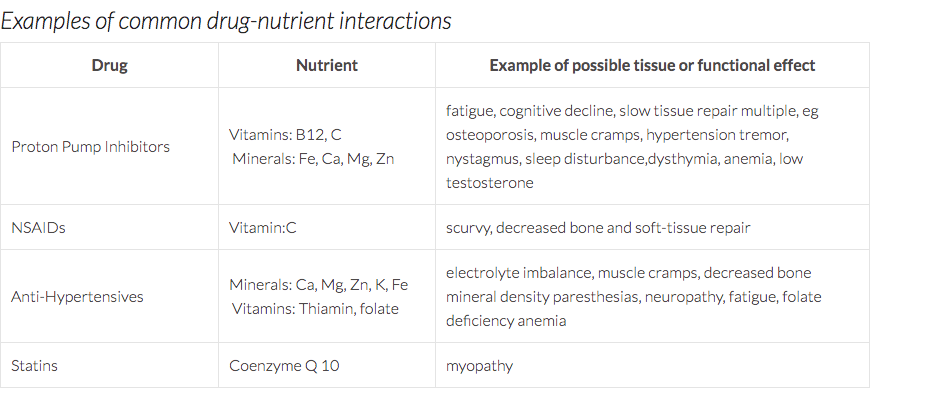

A very common complaint my patients present with is a musculoskeletal pain that, whether the patient realizes it or not, is occurring due to some form of overload or overuse. Tendons are quite susceptible to this. Pain on the outside of the hip, peritrochanteric pain syndrome (PTPS) or pain in the front of the lower leg, medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS), commonly known as shin splints are other examples of this phenomenon. Even when the pain seems to have appeared rather suddenly, the problem has often been building gradually and imperceptibly, until one day, there’s a drop that makes the cup overflow. Healthy tissue is in constant flux. It experiences-- and absolutely needs-- strain from external forces, such as the weight of our body landing on a leg, or the pull of muscles on a tendon. These loads can even cause microscopic trauma, leading to exercise soreness or fatigue. At night, while we are in deep sleep, the body responds to these loads by repairing and strengthening tissue, making it ready to meet the challenge once again. If the strain our tissues experience is greater than what we are used to, our bodies build themselves stronger than before. This is why exercise makes you fitter and stronger, not while you’re working out, but while you sleep, and as long as the repair process matches the strain/breakdown, our body feels good and functions well. Boom and bust Sometimes we may, however, be overly enthusiastic, and rush ahead of our body’s ability to keep up with us through its nightly repair. That new exercise class, or our new running habit, feels good for a while but soon leads to pains and injuries because the body wasn’t given enough time to match its rebuilding efforts to our increasing activity level. The fact that cardiovascular fitness or strength increases faster than tendon thickness or bone strength doesn't help matters either. We can actually train ourselves to run farther, or lift heavier, sooner than what is good for us (or our tendons). Another mistake, unfortunately quite common as well, is to neglect to take into account the varying needs and capacity of our bodies. When we are under some form of stress, physical exercise constitutes an added stressor, and we may both need to sleep more and temporarily decrease our exercise load in order for it to be well tolerated. As we age, and the levels of our anabolic sex hormones testosterone and estrogen, as well as growth hormone, gradually decline, we need more protein and more recovery time in order for our tissues to continue to have a healthy response to exercise (more on that later!). Unfortunately, sleep, especially if not carefully tended to, tends to become more shallow with age, and many 60 and 70-somethings eat less, not more, protein than before. The connective tissue structures (skin, bones, ligaments, tendons etc) of hypermobile individuals are softer and stretchier than those of others, and these individuals therefore need to take even greater care than their less flexible friends to progress slowly but surely, allowing their bodies sufficient time to grow stronger while getting the movement that they need. Tender tendons Tendon injuries are a great example of this process of breakdown due to overuse and under-recovery. When tendon tissue hurts patients have often been told that they suffer from tendinitis. Tendinitis is the inflammation (the suffix -itis indicates inflammation) of a tendon, and results from micro-tears that happen when the muscle is acutely overloaded with a pulling force that is too great. More recent research has demonstrated that, commonly, what ails us is actually a tendinosis, an injury without an inflammatory response (-osis instead of -itis). Tendinosis is a tendon injury that stems from chronic overuse. It is caused by a failed or insufficient healing response of the tendon due to lack of sufficient nightly recovery. The insufficient rebuilding process results in degeneration of the tendon’s collagen, the primary structural protein of skin, tendons and other connective tissue. When overuse continues, leaving the tendon without sufficient time to heal and rest, tendinosis results. Tendinosis often occurs in heels, elbows, shoulders, ankles, hips or knees. Even tiny movements, such as repeatedly clicking a mouse, can, if they are too frequent and too prolonged, cause tendinosis. The same process occurs in the bone and periosteum, the membrane that surrounds the bone, when you get “shin splints” (or, in medical terminology, medial tibial stress syndrome, or MTSS) in your lower leg, or a stress fracture in your foot or thigh. Heel pain due to plantar fasciosis (the ailment formerly known as plantar fasciitis--again, an ailment that usually actually turns out to be an -osis and not an inflammatory -itis) is another common example. Tendinitis or tendinosis - what’s in a name? The reason it is important to know whether what you suffer from is an overuse -osis or not is that it informs the choice of treatment. Anti-inflammatory medication and injections may not be the best idea when your tissues are struggling to heal, especially when your tissues are already slower to heal, as in Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS) or Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD). Inflammation is part of the natural healing response, and in an -osis type tissue breakdow n the problem is actually a lack of a healing inflammatory response. Treatment The problem is caused by overuse or overload, so the treatment naturally has to include--you guessed it-- rest. Athletes in particular hate to hear this, and often re-injure themselves due to not following therapeutic recommendations. Unfortunately, Mother Nature is rather indifferent to our preferences, and until we give our tissues the break they need, they will continue to demand it, either through continuous pain, or through repeated bouts of a similar type of pain. The rest should not, however, mean lying around passively, but rather implies simply decreasing the load on the tendon sufficiently to not cause more pain. During this "relative rest" the tissue has to be appropriately loaded through strengthening therapeutic exercise in order to stimulate that missing healing, repairing and building response so that they will once again tolerate the load placed on them. The exercises aimed at strengthening tendons can basically be the same as the ones used to strengthen the muscles they are attached to. As always, start low and go slow, increasing resistance and challenge as you progress and pain decreases. One thing to not include in tendon rehab specifically is stretching. A strong tendon is a stiff tendon, and hypermobile tendons are already softer than the average, meaning that they benefit from becoming not stretchier, but stiffer through exercise. ...and prevention Since prevention is easier, cheaper, much more fun and less painful than the cure, let’s review some preventive strategies. When starting a new type of movement, or returning to movement, start low and go slow. Hypermobile tissues need more time to respond to exercise, making patience and persistence your best friends in this endeavor. Don’t let impatience get the best of you, and instead give your body several weeks at any given level of intensity or load (weight, time, distance) before you progress. Remember: your cardiovascular fitness may improve faster than your bone density or tendon strength. You also need to prepare your body for movement. Our amazingly adaptive bodies readily adapt to the circumstances they find themselves in, whether those circumstances are floating in the zero-gravity environment of space or frequent or prolonged sitting (decreased bone and muscle mass) or regular, sufficiently strenuous exercise (increased bone and muscle mass. Simply diving into your preferred physical activity may not be the best plan of action. If you sit more than you move, your body is adapted to sitting, and you may need to consult a physical therapist on how to prepare your body by increasing its stability, mobility and specific strength in order to not boomerang back onto the sofa, this time with an injury. Even seasoned exercisers and pro-athletes often have hidden muscle imbalances that put them at risk for both acute and gradual overuse injuries. As an example, decreased control of the hip musculature or trunk puts us at risk for injuries in the lower extremities. Put simply, if some part of your body isn’t doing its work, another part will have to do too much, and may start to break down from the overload More exercise may require more, and/or deeper sleep. Inadequate sleep negatively affects the “stress hormone” cortisol (increasing levels) and growth hormone levels, inhibiting the work of the hormones needed for recovery from exercise and impeding tissue recovery from exercise. From this you can also conclude that if you are going through a tough time, feeling stressed and experiencing trouble sleeping, it may be a good time to temporarily ease up on the exercise a bit. Another sign that you are stressing your body too much can be frequent colds and other infections, as the rising cortisol levels impair your immune system, as well as a decreased sleep quality or increased sleep latency (the time it takes to fall asleep) since elevated cortisol levels impair sleep. Hypermobile individuals are often susceptible to surges of adrenaline as their bodies struggle to maintain homeostasis and these surges may decrease sleep quality. Exercise can slow down signs of aging, but unfortunately it can’t put a stop to the ticking of the clock altogether. Most individuals experience less, and more shallow, sleep, and thus slower recovery from exercise, as they age. With excellent sleep habits this negative trend can be ameliorated somewhat, but most of us should consider giving our bodies more recovery time as we age. And speaking of age, our nutritional needs change as we age, and paying attention to the changing requirements of our older and wiser selves can be very helpful. Adults 65 and older need much more protein to convince their bodies to build muscle. While the protein recommendation for younger adults is 0,8g/kg, current data suggest that older adults need 1,2g/kg, and even a bit more if recovering from an injury or surgery. Perhaps surprisingly, if you are relegated to the bench due to an injury, the amount of protein you need in order not to lose muscle mass actually increases, just like it does during a weight-loss diet. Medications can also impede the absorption of, and need for, certain nutrients. Below is a chart that shows some examples of nutrients deficiencies caused by common drugs, and the effects this can have on tissues If an overuse injury has occurred, or if you simply suspect one, do take it seriously and make an appointment with a doctor of medicine or physical therapy right away. The longer you delay treatment, the trickier it will be to treat. You will rarely see full and permanent success if you treat the injury as separate from the rest of your body, or if you give up to soon. Consulting a physical therapist who can perform a thorough analysis of your musculoskeletal system and uncover the hidden imbalances and glitches that may be causing or contributing to your tissue overload is advisable in all but the simples of cases, and may help prevent future overload injuries elsewhere. The goal is a balanced, stable and happy body that will allow you to exercise and move, today and through the years to come.

7 Comments

|

Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed