|

While some of us have grown up with one hand on the computer mouse and a smartphone in the other, others have more gradually learned to love the virtual world and all the convenience that it offers. Some, like my dear husband, a bit more reluctantly bring up the rear, but for all of us, the virtual world offers both well known, and as yet undiscovered, opportunities. One of these opportunities is called Telehealth. It may also be referred to as Telemedicine or Telerehabilitation. Whatever the term, what it entails is, simply, connecting with your healthcare provider over the internet, usually through video, instead of in a common physical space. Telemedicine has already been in use for several years by everyone from mental health practitioners to medical doctors, but the recent virus outbreak and the subsequent social distancing efforts have catapulted it into our awareness. Thanks to Telehealth, patients, ranging from children with special needs to adults of all ages with musculoskeletal complaints, pain, weakness or balance problems, have been able to continue to receive the care that they need. Telehealth has enabled patients to prevent the worsening of chronic pain, and the loss of balance and function, that a long break in their care otherwise might have caused. Private insurers have fast-forwarded the inclusion of Telehealth into services that they cover, United Healthcare Medicare Advantage just joined the insurers that cover Telehealth, and traditional Medicare may, hopefully, not be far behind. To many prospective patients Telehealth is still a new option. What follows is a list of frequently asked questions, to help you get acquainted with what awaits at the most recent frontier of healthcare, and how you can benefit now. Why should I use Telehealth instead of being seen in a physical therapy office? At this time, one of the benefits is more obvious than ever. Telehealth offers therapy without the need to leave your home, and the recent stay-at-home order, while not preventing physical therapy in a physical office, has made many choose the stay-at-home therapy option. There are many other reasons for having therapy at home. Convenience, saving time, avoiding a difficult or tiring commute are reasons many patients share. Does Telehealth have any distinct and unique benefits? Since a Telehealth session doesn’t require you to leave your home is is a lot easier to fit a physical therapy session into your day. Telehealth brings the therapist into your home and enables her or him to make concrete suggestions for improving your work station, chairs you spend a lot of time in, your workout space etc. If a personal trainer comes into your home on a regular basis, or if you work out at home, you can use a Telehealth session to have your physical therapist review your workout in real time, and make sure it is safe and appropriate, and make suggestions for improvement. Home exercises are reviewed in the actual environment where you are performing them, as opposed to in the therapists office. It may also be easier for a loved one, or other person assisting you, to be present.  So how does a Telehealth session happen? Telehealth sessions are scheduled in exactly the same way that other sessions are, directly with the therapist, or online. You then receive a confirmation email with a linkto a HIPAA compliant, secure website with the simplest program imaginable, called doxy.me . The website works like this: at the time of your appointment you simply click a on link you’ve been given when scheduling a session. (You can click the link here to enter my virtual clinic right now if you like, just to see what it looks like). During the appointment, you may sit in front of your computer to chat with the therapist, and angle the camera of your laptop or smartphone, or stand in front of your desktop computer, so that the therapist can see you, examine you and direct you through exercises.  __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CLICK HERE FOR SIMPLE INSTRUCTIONS FOR YOUR PHYSICAL THERAPY TELEHEALTH SESSION. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Is Telehealth covered by insurance? The good news is that Telehealth is covered by many insurers. Blue Cross and Blue Shield state on their website that they cover these services, and United Healthcare Medicare Advantage plans just announced that they cover Telehealth services as well. Traditional Medicare will hopefully follow suit. As always, it’s a good idea to call your insurance company and ask them directly about Telehealth services (note: traditional Medicare covers something they call e-visit, which is simply a phone call, and is not to be confused with Telehealth). Telehealth services can, like all other services, also be accessed on a self-pay basis. In response to the financial uncertainty many are currently experiencing I am offering pro-rated half hour Telehealth services as well. These shorter appointments are only available to established patients. Can Telehealth appointments be used in conjunction with physical appointments? This may actually be one of the best ways to use Telehealth services. After the initial appointment a patient may not need to be seen in a physical office for every visit, and can effortlessly connect with their therapist from home, their office or while traveling. However, from time to time the patient may have an issue that ideally would be dealt with in person, eg when a manual treatment technique is indicated. If you can click on a link, you can use Telehealth. I’m not very technologically savvy. What happens if I schedule a Telehealth appointment and can’t figure it out? If you can click on a link, you can use Telehealth. The program is extremely simple, and there are just a couple of very simple prompts to follow. That said, if you experience some difficulties with your computer, your internet or any other related issue, don’t worry, we’ll just try again later. You won’t be on the hook for an appointment you showed up for, but couldn’t benefit from because some technical difficulty got in the way. I have my home exercises. Won’t that be enough? Performing a set of home exercises that you were once given is almost never enough in the long run to give you the benefits of physical therapy: avoiding and decreasing pain, ensuring improved and continued function, avoiding injuries and falls, optimizing health, and ensuring that you don’t lose it. Human function is quite complex, and simply performing three or four exercises and expecting them to carry over into your functional movements, your everyday life, is not quite realistic. Due to the complexity of our wonderful, adaptable bodies, that nevertheless remain vulnerable to the challenges of our modern lifestyles, it is simply not possible to teach a patient everything that is needed to meet the challenge of becoming and staying healthy during a few encounters. This is why Physical Therapy is traditionally delivered as a long, or shorter, series of appointments, that build on one another, as understanding increases and function improves, and is often supplemented by less frequent visits as function has been recovered, to keep you on the right track and address smaller difficulties along the way. Home exercises tend to, without supervision and correction, morph into something less effective over time. The patient’s ability and skill grows, and exercises need to be progressed. New symptoms may appear, and need to be addressed, the patient needs to gradually learn how to apply their growing stability, strength or range of motion to their everyday activities, and, speaking of every day: every day tends to bring new challenges, new movements: a trip, lifting visiting grandchildren, a race you’re training for, a new job, a new hobby. As you work your way out of an injury and back to full function, you will need help modulating your activity level —“does this ache mean stop or that I’m getting stronger?” Life is ever changing and fluctuating, and our response needs to mimic that. If you are new to Telehealth, you will be surprised how easy and natural it soon feels! How can I use Telemedicine? How will I know if it will work for my needs? I am, as always, here to answer any questions you may have! Email me, text me (847-208-8063) or call me, or simply schedule an appointment now.

14 Comments

Use it or loose it is an admonition we hear often when it comes maintaning lean tissue (muscle and bone). It It is probably one of the better examples of a a cliche, but the saying does communicate an important truth: our bodies are made for activity, not passivity, and will deteriorate at a surprising rate during inactivity. This is especially true for older adults, who lose lean tissue much more rapidly than the young during periods of physical inactivity. Loss of muscle mass due to prolonged (which may be defined as as little as a week or two during bed rest) inactivity predominantly affects the largest muscles of the body, the muscles of the legs and buttocks. Inactivity also poses a significant threat to our health in other ways, and contributes to everything from cancer to heart disease. It has been even estimated that physical inactivity causes as many deaths as smoking, hence the recent jingle “sitting is the new smoking”. In the population of people 65 years of age and older, decreased levels of physical activity contribute greatly to the epidemic of falls and subsequent injuries. A third of all individuals 65 and older fall each year, and in half of these folks the falls are recurrent. During this time, when the entire population has been encouraged to practice social distancing and work from home, and gyms have closed and everyday movement been minimized, we risk limiting our physical activity and exposure to fresh air and sunlight to levels that pose a threat to our fitness, health and safety. Physical inactivity also increases pain levels in patients with chronic pain. In all individuals, but especially in those with hypermobility disorders it is imperative to not allow the system of stabilizing muscles to atrophy and weaken due to inactivity, as this is a common turning point for increased pain and dysfunction. Exercise has a multitude of amazing effects on our body and mind, and we’d do well to harness these benefits at a time when we all need to support both our mental and physical health. Movement and resistance training to the rescue Physical activity has an effect on almost every organ and tissue in the body. It supports immune system function, is important for mood and general wellbeing and, when performed outdoors, strongly contributes to circadian rhythm entrainment (ie our daily sleep-wake cycle). The best intervention to prevent and treat loss of lean tissue is resistance exercise, which simply means that your muscles are straining against an external force, be it a weight, an exercise band or the weight of your own body moved against gravity, when coupled with an appropriate protein intake. However, sitting all day and only moving once a day for exercise may not do the trick, either, as there is some proof that sitting 13 hours a day or more, easily accomplished especially during social distancing, may undo all the metabolic effects of the exercise and leave you with the elevated levels of triglycerides and blood sugar that exercise normally counteracts. For those aged 65 years and older, it is also recommended that protein intake be increased from 0.8g/kg/day to 1,2 g/kg/day in order to maintain lean body mass. So how much activity is enough to confer beneficial effects? Is picking one activity that you like enough? Think about it this way: what we call exercise is our way of compensating for the lack of spontaneous movement and hard work that evolution has prepared us for, and our bodies consequently expect. Therefore, engaging in only one type of movement, such as walking, is not enough in order to emerge from temporary isolation and inactivity unscathed. Instead, we need variety. All types of physical activity have distinct effects and benefits. The best intervention to prevent and treat loss of lean tissue is resistance exercise, which simply means that your muscles are straining against an external force, be it a weight, an exercise band or the weight of your own body moved against gravity. DAILY EXERCISE ROUTINE What follows is a program that will help meet your body’s need for frequent movement through the day, movement for circulation, cardiovascular health and immune system support, and maintenance of lean body mass. It is divided into three sections, with the section for strengthening divided into two subcategories. The sections offer activities of varying levels of difficulty and a chance for variety. Choose the most appropriate levels for you --you should be working hard but be able to maintain good form, or quality of movement,-- and make sure to pick one choice from each group. All exercises should be pain free, but mild soreness at the beginning of an exercise is fine. Follow the traffic light guidelines to distinguish between innocuous soreness and pain as a sign to stop. Two exeptions to be aware of: perform all three stretches daily, but perform strengthening exercises only every other day if you are able to perform them at an intensity that gives you a bit of exercise soreness the following day. GROUP 1- Frequent movement through the day

GROUP 2 - “Aerobic exercise” or prolonged higher intensity movement Best if performed outdoors when practical and appropriate (note that future directives for social distancing may include avoiding time outdoors, and even in the absence of such directives you should follow the advice calling for keeping a distance of at least 6 feet between yourself an others).

GROUP 3- Strength training The most important muscles to strengthen are the muscles of the buttock and legs. Stabilization exercises:

GROUP 4 - Flexibility

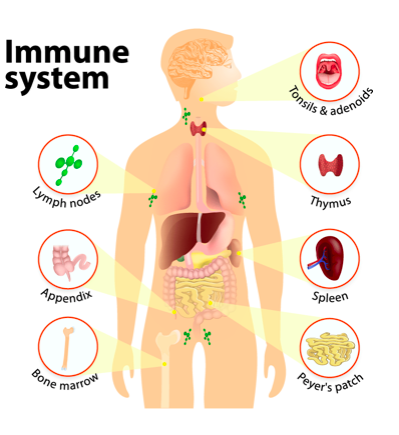

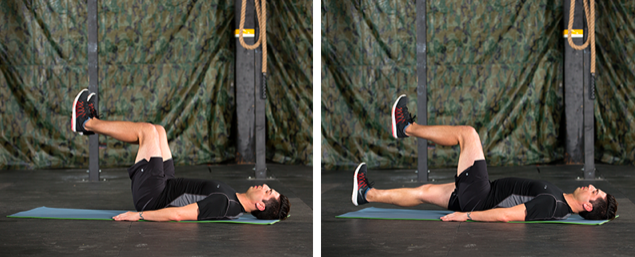

All types of physical activity have distinct effects and benefits. No one type of activity offers all the benefits you need. IMAGE GALLERY FOR THE EXERCISE PROGRAM Trunk stabilization exercises

Trunk stabilization: lie on your back, pace a pillow under your head as needed. Gently tighten pelvic floor, keeping hips and knees bent as shown in first photograph. While making sure to not allow low back to arch, slowly move one leg at a time away from the body, and return. Emphasize correct form, not moving the leg so far out that you arch your back. (Second photo shows advanced progression, initially lower your leg only few inches. Progression depends on your ability to keep your low back stable against the floor)

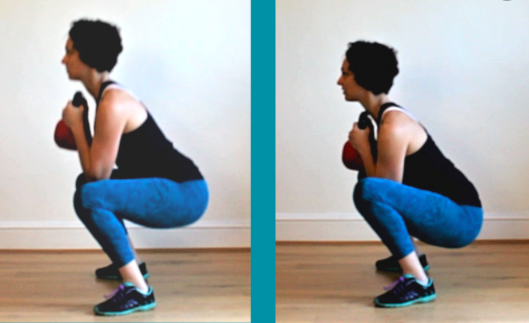

The single leg squat is a progression of the above lunge shown in the previous photo. Place one leg on a bench, sofa or chair and lunge down, again keeping in mind that the knee must track in line with the foot, not to the inside of it it! Prioritize correct form over trying to squat more deeply. Stretching or "Strelaxing" (aka a relaxed stretch) Succesful stretching means relaxing muscles, not pulling them. The stretching position allows you to feel the muscle, the stretch itself consists simply of your conscious relaxation of the muscle. Think "melting', or imagine the body part growing heavy. Hold stretches for 2 minutes or more. Chest stretch (specifically for the small chest Mobilization of the upper back. Roll up a yoga muscle, pectorals minor, that greatly contributes mat, and place it under your upper back (you to limited shoulder movement). Lie down as can vary the exact position for bets effect). shown, place a pillow/pillows under your arm as Bend back to straighten the convexity of your needed. The arm must be supported.Tip hips upper back as shown. This is a back and forth towards opposite side to increase stretch motion, not a static stretch. as needed. A comfortable variation is simply placing a folded up towel under this part of your back and relaxing with arms stretched out and hips and knees extended, or, if needed, bent. Hip flexor stretching. Choose either option as illustrated above. The stretch is diffuse and felt across your groin area. Remember to remain comfortable and relaxed. Stretching is about relaxing muscles, not pulling or forcing. Those hypermobile individuals whose hips joint tend to subluxate forward should be careful not to lunge forward to far and too deeply while performing a single leg squat or walking or stationary lunge, and should keep their upper leg supported by the bed in the image above, completely avoiding hip stretch option number two. ***** Remember: there is still much to enjoy, and stressful times can also contain good times. Enjoy the things you can do, things you perhaps now have the time to do. Enjoy the time with, and exercise together with, your family members. By balancing activity with relaxation you will support both your musculoskeletal system and your emotional health Related note: the significant difficulty I experienced finding photos for this article, correctly demonstrating a particular exercise or stretch, reminded me of how much incorrect advice is circulating on the internet. Be discerning when taking in such information, and always consider the source. New threats, powerful defense We’re living in times when our trust that the healthcare system can offer us fast and reliable solutions for any pathology is waning. We’re facing antibiotic-resistant bacteria and an alphabet soup of new viral epidemics--SARS, MERS, H1N1, Zika, Bird and Swine flus, and now COVID-19--with no pre-existing therapies or readiness, prompting us to seek solutions elsewhere. Panic and hoarding are understandable, but not very protective behaviors. Fortunately, drugs and vaccines are not our only defense against microbes. Like all species we, too, have evolved in a world full of microbes and developed our own innate defenses against them. Even when medical and pharmaceutical treatments are available, they are largely dependent on the strength of the body’s innate workings in order to be successful. Instead of emptying store shelves, let’s arm ourselves with a few facts about the power of the immune system so that we can do our best to support it in ourselves and in our loved ones. The immune system - another miracle at work We are continuously exposed to pathogens, ie microbes that have the capacity to cause us harm. They evolved long before plants and animals did, and because of this all species in existence have evolved with defensive strategies against potential infections. This is what we refer to as our immune system. The immune system is spread throughout the body and involves many types of cells, organs, proteins, and tissues all working together to keep us safe from harm. One of its crucial features is that it can distinguish our own tissue from foreign tissue — self from non-self. An antigen is any substance that can spark an immune response. In many cases, an antigen is a bacterium, fungus, virus, toxin, or other foreign body, but it can also be one of our own cells that is faulty or dead. White blood cells of various types play a central role in recognizing, remembering and destroying these foreign invaders. Certain types of white blood cells make antibodies, which mark particles as foreign invaders, while other types of white blood cells kill and engulf the invader, and dispose of it. Most of the time our immune system works so well that we don’t even notice it. We are not aware of the cancer cell it destroyed, the cold virus it killed so that we didn’t get sick, or the balance it’s striking between protecting us from non-self particles while sparing our own cells. But like any system, its delicate balance can be affected by many aspects of our lifestyle.  What impacts the immune system? Immune system function varies over the course of life, with newborn babies depending on antibody protection through nursing, many lifestyle factors common among adults taxing the immune system and many, although not all, people over the age of 65 experiencing some immune dysregulation that makes them less able to respond to immune challenges. This also manifests as a decreased ability to create antibodies and a resulting diminished response to vaccination in older adults. Medications such as cortisone, other immunosuppressant medications, chronic stress, malnutrition, loneliness, overexertion, a sedentary lifestyle, overuse of alcohol and poor sleep and irregular sleep/wakefulness cycles (aka circadian rhythm dysregulation) are some of the more common factors that can tax this powerful system and prevent it from effectively defending us from pathogens. Can you “boost” your immune system? The answer is generally “no”, but more importantly, you wouldn’t want to. An overactive immune system means feeling inflamed, unwell, allergic or experiencing an autoimmune reaction. What you do want, however, is to make sure your immune system functions properly. The effects of nutrition on your immune system Not unlike other bodily functions, the immune system is dependent on certain nutrients. While few individuals in the developed world are dying of hunger, lifespan and quality of life may for many be affected by poor nutrition. It has been estimated that 35% of those aged 50 years or older in Europe, USA and Canada have a demonstrable deficiency of one or more micronutrients . Children may suffer from vitamin and mineral deficiencies due to selective eating habits or lack of sunshine, and the elderly tend to eat less food, but still require the same amounts of micronutrients (and even more protein than younger individuals), which can make for a tricky equation to solve. Micronutrients that are especially important for immune system function include:

Please note, however, that healthy eating habits and supplementation can only support normal immune system function by supplying it with the building blocks it needs to function. You can not build some kind of super immunity by supplying your body with higher than physiologically necessary amounts of these nutrients, or any other interventions either, just like, while sleep deprivation can make you more susceptible to infections, sleeping more than necessary won’t increase your resistance to infections. Inflammaging Inflammation and aging seem to go had in hand, leading to the concept of inflammaging, an imbalance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory networks contributing to common age-related changes, including immunosenescence, or the aging of the immune system, which, as mentioned, contributes to the increased susceptibility of many older individuals to infectious disease. Anti-inflammatory nutritional interventions can therefore be useful. Fortunately, the aging of the immune system is quite malleable, and affected by both lifestyle choices and medications. In patients with diabetes the immune system is suppressed by the elevated blood sugar levels. Metformin is a drug commonly used to counteract this phenomenon. The herbal compound Berberine has similar effects, leading to speculation that it could help non-diabetics keep blood sugar levels at ideal levels and thus support the immune system. Physical activity exerts an anti-inflammaging effect via several mechanisms. Studies have also shown that individuals who perform regular exercise appear to be at a reduced risk of mortality from infections. Exercise also tends to raise Human High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) levels (levels of what many like to call “good cholesterol”). HDL has both anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects. Other ways of attenuating inflammaging include avoiding caloric excess and eating a nutritious diet. Diets like the Mediterranean diet or other personalized diets with nutritional supplementation with micronutrients and limonene have been shown to both decrease inflammation and improve immune responses. In summary…. Anyone wishing to improve their body’s resistance to infection and illness, whether chronic or acute, can benefit from first and foremost supporting their body’s basic functions by ensuring sufficient levels of nutrients through both diet and supplementation, as well as observing other healthy habits and practices that allow the body to function optimally. Even when a vaccine exists for a particular disease, it is the person’s own immune system that creates the antibodies, and a weak immune system is less able to do so, leading to an antibody response after vaccination of only 17–53% among the elderly. Regular sleep/wake cycles supported primarily by appropriate exposure to light and darkness, supporting sleep, which I’ve written about here, movement, spending time in nature and avoiding loneliness and stress are all powerful tools. Older individuals need to be especially mindful of taking good care of their immune systems, and this includes taking steps to reduce inflammaging. Exercise regularly, move often, give yourself reasons to laugh even more often, eat well and supplement wisely. Did I forget anything? Comment with suggestions here!  As a hypermobile person you may be used to feeling different. Your balance may be less than impressive; your joints and muscles ache for what seems to be no good reason; and, yes, it’s your hips making that clunking sound when you’re trying out the latest exercise your more normal-jointed friend is excited about. You also experience a vast array of non-musculoskeletal weirdness that never ceases to mystify you and those around you. You may by now be well aware that you need a different approach to exercise than others, focusing much more on stability than marathon running, and your collection of splints and special pillows has been growing at an impressive rate. With all of the special attention that your body seems to be demanding, it is easy to forget that it is, still, a body that requires and benefits from the same loving care and attention that human bodies, in general, do. As a matter of fact, your body may benefit even more than that of your less bendy friends from supporting its basic functions. Let’s review the four cornerstones of health: sleep, diet, exercise and mind management and some of the ways you can help your body serve you well. Please note that the following is a general overview and not intended to be a comprehensive list of all the comorbidities associated with HSD/hEDS, but rather as a reminder of the importance of general, supportive health practices. Sleep Your soft ligaments, joint capsules and tendons are less able to protect themselves and more easily sustain small injuries, so called micro-injuries. While your spouse or friends seem to get away with a lot of slouching, following their lead reflexively triggers your muscles to work overtime. Your nervous system is straining to maintain homeostasis and your blood circulating in your stretchy veins. Night-time constitutes a well-deserved break for your hard-working body! Deep sleep is when tissues rebuild and repair themselves, and sleep deprivation therefore impairs your body’s ability to sufficiently regenerate tissue overnight. Accumulating, un-repaired, tissue damage leads to pain and soreness, and may even over time contribute to a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Artificial light at night, the light pollution that seeps through our curtains while we sleep, has been found to contribute to breast and prostate cancer, obesity and depression. Sleep is also a time for your brain to recover from the events of the day, and for learning (say of those balance and stability exercises you’ve been doing) to be consolidated into long-term memory. And honestly, the very last thing you need when dealing with the demands of a hypermobile body and chronic pain is one of the most reliable outcomes of poor sleep quality, the significant negative effect it has on mood. So here, shortlisted for your convenience, are the ingredients of a good night’s sleep:

Diet Put simply, your food gives you the building blocks that your body is made of. Genes that code for softer connective tissue seem to be implicated in hypermobility disorders such as HSD (Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder) and hEDS (Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome). The softer connective tissue is itself more easily damaged by over-stretching, and also puts the joints and muscles it is meant to protect at risk. This creates an increased demand for effective healing of tissue. It is therefore important to make sure that your body has a steady supply of the necessary building blocks needed for tissue regeneration. The most important building block of connective tissue structures is collagen, the very fiber that makes your body different. Moderns diets tend to contain less collagen than traditional diets, and collagen supplementation can therefore be a safe way to increase collagen turnover. Vitamins C and D are also needed for collagen synthesis, and supplementation of these micronutrients may be beneficial. Hypermobile people often suffer from gastro-intestinal (GI) manifestations of the softer connective tissue and associated disorders, such as delayed stomach emptying and slower motility — the movement of the food through the GI tract — leading to discomfort, bloating and constipation. Eating smaller portions, avoiding snacking, and allowing your system a break from eating through a long overnight fast can be helpful. Ginger is a safe and tasty root that improves gastric emptying and motility and can be used both as a tea and a supplement in capsule form. Overweight is never healthy, and with a hypermobile body it can cause additional problems. Extending the overnight fast to 12-14 hours, and especially for men, who seem to tolerate longer fasts better, up to 16 hours, can be a simple way of improving insulin sensitivity and your body's ability to handle energy. Many hypermobile individuals notice increased thirst, especially when under stress. Blood pooling in the lower half of the body may trick the kidneys into thinking there is too much, when there is actually too little. Chronic dehydration, fatigue, headaches and dizziness can also be a sign of Dysautonomia. The softer bladder may both signal the need to empty it more frequently, and also empty less completely. This can predispose the individual to UTIs, or urinary tract infections. Drinking a lot of water can be helpful in diluting the urine in the bladder and potentially help prevent UTIs, but can also dilute the electrolytes in the body, leading to a vicious cycle of increased thirst and increased dilution. This can in turn exacerbate symptoms of feeling faint and dizzy when standing up due to orthostatic hypotension or POTS. Adding minerals or electrolytes to your drinking water can be helpful. Some electrolyte brands even come with small travel bottles that are easy to carry in a purse or pocket. Salting your food generously, adding salty foods like olives and pickles, and even taking salt as a supplement can all be of great help. Sodium has been demonized and many initially fear adding more to their diet, but when it ameliorates symptoms without elevating your blood pressure you have little to fear from this important mineral. Exercise Our bodies are designed with the expectation of movement, and simply cannot stay healthy and function well without it. This is just as true for hypermobile individuals as it is for others, but hypermobility presents an added layer of complexity for the would-be exerciser. While it is true that all human bodies require stability, hypermobile bodies rely more heavily on muscles for both proprioception and balance and joint stabilization. If the muscular system faces this challenge untrained, certain muscles are likely to be overburdened and become tight and sore, while leaving joints poorly protected. Instead of simply looking for a type of exercise that seems like fun, we should create a body that is prepared for exercise. The best place to start is with slow, well-controlled exercises that first stabilize the pelvis/spine/trunk, and then the shoulders and hips. Be aware that while the neck is simply the upper part of your spine, it is also closely connected to your shoulder girdle and therefore affected by any tightness and weakness in this area. The most effective way to approach this is through an individualized program based on therapeutic exercise and natural, functional movement, prescribed specifically for you with an understanding of your specific needs, and progressed as you improve. This program should also contain a strong focus on balance and proprioception, and not be seen as a static set of exercises, but a gradual, progressive challenge to your body to help it serve you well. Attempting to meet your individual and specific needs through generic movement programs, however popular, may not be quite as effective. Hypermobility is a trait that can have serious consequences and should be treated by degreed healthcare professionals with a thorough understanding of the human body and familiar with the particular set of traits characteristic of hypermobility. The most fruitful way of seeing any challenge you may have is not “my diagnosis explains my symptom and condemns me to always have it” but rather, “my diagnosis informs and inspires me and means that I have to work even harder on helping my body function optimally”. Which leads us to the mind. Mind Just as a hypermobile body means that you may have to pay more attention to exercise than the average person, the added challenges you face also mean that you will benefit more from actively controlling your mind. The quality and quantity of your sleep is, as mentioned, the sine qua non of a positive mood. Creating an internal locus of control, a sense of empowerment and of not being at the mercy of others, is another important cornerstone for good mental health and thriving. Information is one of your most important tools in this quest. Understanding, not just the basics of your diagnosis, but the repercussions of it for your body in general, is important for your ability to understand and manage symptoms. Hanging your hat on the hope that someone else, some expert, will give you the key to feeling good is looking for fool’s gold. Experts are invaluable as a source of information, but no-one will ever care as much about or know as much about you as you do. Stay on the path of learning and experimentation, gradually adding good habits and beneficial practices to your life as you go. Set goals and be proactive instead of reactive. Simply reacting to pain and dysfunction can feel hopeless and disempowering, while creating a plan for gradual growth and improvement is inspiring and helps you gradually reach functional, meaningful goals. Joint hypermobility is strongly correlated with anxiety, even in animals. This correlation is probably, at least in part, if not entirely, the result of over-activity of the sympathetic nervous system (the “fight or flight” part of our nervous system). Consciously seeking to counteract the potential negative effects of this on our mood and body is arguably an important part of hypermobility self-care. Calming and centering practices such as meditation, slow breathing, slow walking (a pace of under 3 miles/5 kilometers per hour), and slow, repetitive activities, (e.g., knitting, reading, or t’ai chi, can support the parasympathetic (“rest and regenerate”) part of our nervous system. The synergy of the four cornerstones It can be tempting to focus on one of these cornerstones more than others, for example seeking information more than relaxation. Some people rest too much and exercise too little, while others tend to do the opposite. The four cornerstones of good health are, however, synergistic in nature. Sleep is what allows your body to benefit from exercise, retain information and good mood. The dietary building blocks allow you to build and repair connective tissue, and your exercise trains your body to put these tissues to good use. Creating good habits and achieving a good balance allow you to manage problems, improve, and even thrive. Gather information, become informed, use experts as teachers and guides, but always remember that you are in charge. The path is yours and yours alone and you have a greater influence than anyone else on where it will take you!  You’re faced with a health concern you can’t quite figure out on your own. Maybe you have a bacterial infection, or perhaps a tendon is aching from all the running you’ve been doing. Where do you turn for help? What reasoning do you use to discern what to believe and trust among all the voices vying for your attention? In the day and age of concepts such as “fake news”, many people are left with the (fortunately erroneous!) impression that there is no consensus in the health sciences either. This article is intended to help you approach taking care of your body, in sickness and health, and finding the help you need to do so, in the most logical and effective way, and in the process help you avoid the many potential pitfalls along the way. When it comes to the serious infection, most people tend to turn to a medical doctor. They know that by doing this they have chosen a professional that is a graduate of a rigorous program and who will base their recommendation —probably a course of antibiotics — on scientific evidence, not on best guesses or hearsay, or on what some other person told them. This practice, basing your actions on scientific evidence in addition to the traditionally honored practices of clinical knowledge and the patient’s desires, is called Evidence Based Practice. Evidence Based Practice therefore strongly incorporates and emphasizes the scientific method; systematically testing a hypothesis and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once such as study has been performed, scientists seek to publish their findings in the form of a scientific paper in a peer-reviewed journal. Many different studies then accrue over time, and other scientist authors summarize these many studies into one, and draw conclusions based on these. If 20 studies point to A, and only one, poorly designed, study points to B, we have good reason to conclude that A is correct. We don’t, however, rest on out laurels, and scientific evidence is continuously accumulating, ever refining and enhancing our understanding. Experts back their claims with scientific references The above system also leads to a hierarchy of evidence where the opinion of an expert ranks the lowest and systematic reviews the highest. The latter is also what is later used to base practice guidelines on for various types of practitioners, and any “expert” worth listening to also continually refers to the highest levels of evidence to back their claims. Even lay persons can access many of these scientific papers eg on Pub Med https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed.html .PubMed is a free resource provided by the NIH for peer-reviewed biomedical and life sciences literature “with the aim of improving health – both globally and personally.” Unfortunately, the lay press often contributes to the confusion by focusing on individual case control studies and expert opinions, creating among their readers the impression that our scientific consensus is weak and ever changing. Because.... science All this means that when you are turning to your medical doctor for help with that serious infection, you can rest assured that her or his recommendation is based on sound scientific evidence, not tradition, guesswork or dogma. You certainly wouldn't have someone with self-proclaimed surgical expertise remove your gallbladder. You'd insist on a professional with a degree proving his or her expertise. This is the rigor with which you arguably should approach all aspects of your healthcare. Scientist have gradually worked to understand physiology, biochemistry etc, other scientists have critiqued and refined their work, and a large body of evidence has accumulated. Your physician has not only received a specific degree based on this, but is also receiving periodic updates to their practice guidelines. All this to make sure that your care is up to date, based on the best of our knowledge today, not on assumptions an not on beliefs that were held 20 years ago. How about that aching tendon then? When it comes to musculoskeletal issues, there are many, mostly well-intentioned individuals who, thanks to the world-wide web, have found an unprecedented outlet for their creativity. While, in the times before personal computers, only credentialed individuals with formal expertise in any given area were given a platform, usually in the form of publishing a book on any given topic, today anyone with a computer can post videos on Youtube or create entire websites dedicated to their ideas. Any self-proclaimed guru with enough marketing savvy can easily reach an audience large enough to create a course, claiming to certify (usually after a brief course of study), that the certified individual possesses some type of expertise (has become a certified practitioner or expert of this or that). Convincing as this may sound, a brief course on any given topic doesn’t come anywhere near the knowledge base of a practitioner with a multi-year formal academic degree, based on a rigorous science-based program. Unfortunately this is not always obvious to the unsuspecting audience, which instead may be influenced by a convincing tone or a captivating video. Appearances matter a lot these days, and coming up with a catchy name or slogan goes a long way - just not towards creating good health. Don’t fall for easy tricks and simple claims - your body is not simple The greatest enemy of truth, however, tends to be our increasing appetite for simplistic explanations, concepts that can be grasped immediately, without the pre-existing context of a scientific understanding. But the human body is incredibly complex, and any intervention, any concept, any approach that is based on actual scientific evidence is therefore, by definition, going to be complex, not something that is easy to generalize and sell. And at the end of the day, Mother Nature follows her own rules, and only by following those rules can we safely obtain the results we are looking for. So, with the infection cured by antibiotics, to once again be able to run without pain or injury in that tendon, you need to find out how to proceed. Should you look to various movement practices? Will yoga have the secret sauce? Should you, as your friend recommends, simply rest, because running, she says she's heard, is bad for you anyway? Is there one simple trick you need to find somewhere? Fortunately, while you may not be sure how to proceed, as your area of expertise may lie elsewhere, science does. While there is a lot left to learn, we do know quite a lot about tendons, and we do not need to waste time, as the saying goes, “throwing some stuff at a wall to see what sticks,” trying various dogmatic approaches that claim that their movement philosophy is the cure-all. We know that tendons have a certain ability to accept and transmit load (eg the pulling force through it as you’re running). We know that tendons, over time, change according to the load you place on them (inactive people have thinner tendons and ligaments than people who place a great load on their tendons, eg by running or lifting weights). We know that tendons ail (we call this tendinopathy) when the forces we place on them exceed their strength, and their ability to repair overnight. We know that to heal tendinopathy we need to temporarily decrease the load while gently stimulating the tendon to grow stronger. These basic facts are no less true, but actually more so, in specific cases such as chronic pain, joint hypermobility syndromes, aging etc. Individuals that fit into these categories need to take even greater care to be guided by properly trained healthcare professionals. Consider the source Can those two funny guys you found on youtube guide you through this? Maybe, although unlikely, but how can you tell whether what they are saying is correct or not? You consider the source, and the sources your source uses. If that sounds complicated, here’s what it means. You consider what, if any, credentials the individual has. Have they gone through a long academic program in order to obtain a, preferably terminal, degree specific to the claims they are making? Are you listening to a DPT (Doctor of Physical Therapy), MD (Medical Doctor, preferentially with a specialization in orthopedics of physiatry), DO (Doctor of Osteopathy), DC (Doctor of Chiropractic) or ND (Naturopathic Doctor), or are you listening to someone who never mentions their credentials because they don’t have any? If the latter is the case, you are most likely placing your health in hands that lack the requisite competence. I have the utmost respect for autodidacts, and to a certain extent we all have to be responsible for broadening our scope of knowledge and understanding in order not to endanger patients through the almost absurd degree of specialization that exists in health care today. Certainly not all knowledge that is worth sharing has to obtained through formal education. But in order to gain your trust, your source should always at least be able to tell you why they are making the claims that they are. “Everyone knows”, “I’ve noticed” or “I learned this from someone I really trust” are not scientifically valid arguments. So here are some things to think about and look for when you are about to place what is arguably one of your greatest assets, your health, in the hands of someone, trust their claims and follow their advice:

Once again, the body is complex, and those of us who have devoted years of study and practice to understanding the body are in awe of its complexity and ingenuity. We do not believe that there are easy and quick fixes, nor do we advocate one size fits all approaches. We stay attentive to new research as it emerges and make changes to our clinical practice accordingly. And when our patients ask us for advice, and ask us where our information originated, and why we make the claims we do, we can usually refer to science. We make a clear distinction between our clinical observations and practice guidelines, whether we agree with them or not. Most of all, we value the knowledgeable patient, and always strive to both educate our patients and help them become a discerning and educated audience for health-related claims, whoever is making them. To this end, our patients have to understand how we arrive at our conclusions, claims and practices. They have to understand the basic structure of the scientific process and it’s clinical application. My hope is that this article has been helpful with that. To your health, and your knowledge and understanding thereof! Few topics stir as many emotions and awaken as much fear, hope, confusion and even judgement as our diet. The overabundance of opinions, dogma and conflicting claims repels and confuses us, yet we, justifiably so, feel the need to make sense of it all. We have always known that diet is indeed one of the cornerstones of good health. The founder of western medicine, Hippocrates, well over two thousand years ago strongly emphasized the fundamental role of food and exercise in health. Food is also one of our greatest sensory pleasures, one that brings people together and celebrates our connection to the natural world. To sort it all out, let’s first consider why we eat, and why we should pay attention to what we eat, in the first place. Food serves several functions: it acts as a source of energy for the body, it serves as a building block for our constantly renewing tissues and it gives us ingredients that facilitate various other processes in the body, among them thinking, hormonal function, reproduction etc. But in a time of relative abundance, we tend to turn our attention from these important roles and focus more on the shadow side of food; the fact that, when eaten in quantities larger than what we need, it can wreak havoc on our bodies and cause negative effects such as obesity, inflammation, and diabetes. This often colors out relationship with food and leads us to think of it not as a life sustaining force but as something of a threat. “Are eggs bad for me?” we ask. “Will carbohydrates harm me?”, “Will eating meat give me a heart attack?”. As is true for most choices in life, choosing our diet based on fear, without a clear paradigm, can have us running back and forth like a ball boy at a tennis match, vegan this day and keto the next, enthusiastic about the newest food religion one day, fearful that we may still not be getting enough of the latest superfood the next. Choosing a diet based on what it doesn’t contain is arguably not enough. Thinking instead about what our bodies actually need (the “macronutrients” fat, protein and carbohydrate as well as “micronutrients” such as vitamins and minerals), and how to get enough of each type is the only logical and comprehensive approach. Humans evolved over a very long period of time eating an omnivorous diet, consisting of a wide variety of plant foods and animal foods, sometimes with a bit more to eat, sometimes going for a little while without food. While our genes haven’t had time to change much (read: we still thrive on a very similar diet to the one we evolved with) there have also been some relatively recent changes in our genome, and as opportunistic omnivores we inarguably have much more leeway when choosing what to eat than a single-plant eating panda bear. While there is no need to buy into the latest egg or lectin scare, there are some things that make their way into our food that we would do better without. These include certain, potentially problematic, (inflammatory, neurotoxic, xenoestrogenic, carcinogenic) non-food aspects of the modern diet. They have less to do with the food items we eat and more to do with how we grow and handle our food. Modern additions to our diet that we did not evolve to tolerate well include things like vegetable seed oils (sunflower-, corn- and safflower oils etc), synthetic trans fats, an abundance of processed acellular carbohydrates, an abundance of refined sugar, pesticides, food coloring, preservatives, pasteurization, and so on. We would do best to view these more recent additions to our lives as science experiments we choose not to participate in. Uniquely nutritious food items no longer ubiquitous in our diet include organ meats and collagen-rich organs like bone, skin and tendons, and making up for this loss may support optimal health. While science is usually a good starting point for understanding our world, food science is unfortunately not best known for its rigor and quality. Fortunately we do know a great deal about the human body and what it needs, and can most certainly nail down some basic facts. Instead of looking to self-proclaimed gurus espousing complicated diets based on the purported dangers of this or that food item, we might do better to look to our ancestors and our bodies for answers. Let’s take a big step back and consider a few facts:

There you have it. Like the author Michael Pollan famously said: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” Get enough protein, including collagen, good, natural fats, plenty of plant foods. Consider who you are (your age, activity level, injuries and recovery, body type etc) and choose your macro- and micronutrients accordingly. Eat fresh, organic, grass fed - you know, whatever your great grandparents would have recognized as food. Avoid unnecessary chemicals such as pesticides, preservatives and food coloring whenever you can, and listen to your body. Love food, don’t fear it, and it will love you back.  In a world where we are swimming in a sea of advice and admonitions, how do you sort through all the information? How do you decide what is relevant to you, and make good use of it? Seemingly contradictory advice abounds, threatening to confuse the most analytical mind. Should you try the carnivore diet, go vegan, or fast? Should you follow your own daily rhythm and stay productive until the wee hours of the night, or go to sleep when the sun does? What is often lost in the rush to present a never-ending stream of new, fresh ideas is the fact that there are some unchanging foundational requirements for health. This a basic principle that no new dogma, product, or guru can change. 80 percent of results come from 20 percent of foundational effort The 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle, states that 20 percent of the effort you put into any endeavor leads to 80 percent of the results, and conversely, that 80 percent of your effort only leads to an additional 20 percent gain. How does this apply to your search for health and well-being? It means that you get most of the benefits from a few simple things. After these fundamental requirements are met, we benefit relatively little from adding the latest exotic bells and whistles. It therefore stands to reason that we should be paying much more attention to the basics, and much less to the siren song of the new, the expensive, the popular or the latest health fad. So what are these fundamental principles, our 20 % that will give us 80% of the benefit? The four cornerstones of health are sleep, diet, exercise, and the health of your mind. Let’s start with sleep, and cover diet, exercise and the mind in subsequent posts. “There is a time for many words, and there is also a time for sleep.” ― Homer, The Odyssey Deep sleep is when tissues rebuild and repair themselves. Sleep deprivation therefore impairs your body’s ability to sufficiently regenerate tissue overnight. Accumulating un-repaired tissue damage leads to pain and soreness, and may even over time contribute to a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, or simply looking like, well, you know what. As mentioned in a previous post, sleep is also a time when the brain is cleansed from metabolic waste, making sleep not just one of the best tools for rebuilding the body, but also the brain, protecting us from everything from unhappiness to dementia. Artificial light at night, the light pollution that seeps through our curtains while we sleep, has been found to contribute to breast and prostate cancer, obesity and depression. Sleep is not only a time for your brain to recover from the events of the day, but also for new information (for example, those new exercises you’ve been doing) to be consolidated into long-term memory. And honestly, the very last thing you need when dealing with the demands of your career, your young children or a surreptitiously aging body, is one of the most reliable outcomes of poor sleep quality, the significant negative effect it has on energy and mood. So here, shortlisted for your convenience are the ingredients of good sleep. These are fundamentals that the night owls among us need to adhere to even more strictly than others, as their circadian rhythm more easily is disrupted by artificial light at night. The ingredients of a good night’s sleep

If you have been lax with your sleep hygiene, kept late hours or have suffered from insomnia for a while, keep in mind that it does take time for us to change habits and expectations. Make positive choices and give them several weeks to gradually work their magic. Remember, good health is not the result of easy shortcuts but of lifelong, conscious habits. Now that is something worth sleeping on! BALANCE, STABILITY AND COORDINATION - THE SECRET SUPERPOWERS THAT KEEP US SAFE, STRONG AND UPRIGHT12/8/2019 Proprioception - a fancy term for a very useful sense Do you think of yourself as having good balance and coordination? Most people who rate their coordination as ‘very good' tend to be physically active, doing sports or a demanding form of dance on a regular basis. Others feel that the movement of their bodies is less than precise, like those of an awkward teenager after a sudden growth spurt. They experience difficulty calculating their height and width and constantly bump into things or often knock things over. Maybe you’ve always though of yourself as clumsy and uncoordinated, or perhaps you’re one of the many who seem to, over time, have misplaced a previously good sense of balance and now limit your activities due to a fear of falling and hurting yourself. In order for us to move in a coordinated fashion, we have to know where our body is at all times. Our proprioception makes this possible. Proprioception is our ability to feel the position of our body in space, as well as our body’s movement through space. (This ability to sense movement is also called kinesthesia, from the Greek words for movement and sensation.) Proprioception is the reason you know where your body is in space, and what position it is in, even when your eyes are closed. This system provides the necessary information for the control of posture and movement both consciously and unconsciously, and it is thanks to this amazing ability that we don’t keel over the moment the lights go out and we no longer can see our body. noun: proprioception

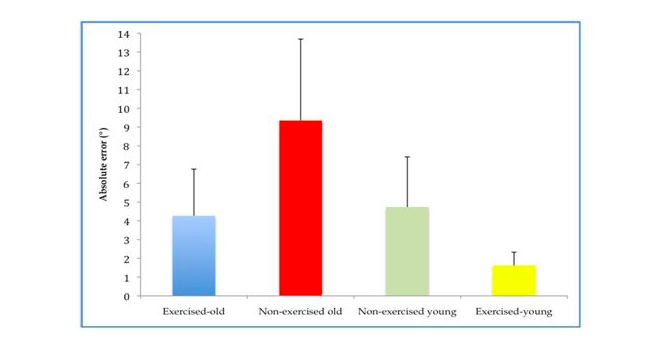

The stuff that balance is made of Mechanoreceptors are tiny, specialized sensory receptors that are located within joints, muscles (muscle spindles), ligaments (Golgi tendon organs), joint capsules and tendons. They communicate information about pressure and tissue lengthening to the central nervous system (the brain and the spinal cord), creating proprioception. The deep layers of the skin and the fascia, (the connective tissue layer that covers our muscles and organs and tie the body together as if though through a three-dimensional fishnet), also act as supplemental sources of information for our sense of proprioception. This system helps us both stand, walk and move while our conscious attention is focused on something else, and create precise movement at will. It helps us use just the right amount of muscle tension, and use our joints in a manner that is precise enough to not overload support structures such as ligaments. It helps us balance our tall bodies against the downward pull of gravity, and balance our head on our neck without unnecessary muscle tension and ligament strain. Balance is an important skill, and most commonly needed in the form of what physical therapists like to call single limb standing, ie standing on one leg. Whether you would like to walk, run, step over or into something, be it a bathtub or a pair of pants, you need to be able to balance your body on one leg. The ability to do so is a skill, and skills are composed of many components. You need the raw muscle strength of muscles such as the gluteus medius, a (as the name implies) medium-sized buttock muscle that helps keep the leg straight underneath you. You need proprioception, the understanding of what is going on based on all that information flowing to your brain and spinal cord from the mechanoreceptors throughout the body, and you need the ability to pull all that together into a movement program, created in the motor cortex in you brain. The motor cortex is where the software for our movements, or motor programs, are stored, and this software is constantly either being improved or deteriorating, depending on how much and how well you use it. When the system fails That is all fine and good, the uncoordinated and poorly balanced among us may say. Amazing as this system may be, I am still having trouble with my balance and my coordination, so what gives? This is a question with many potential answers, so let’s go through them one by one. In certain individuals one reason proprioception, and therefore balance and coordination, may be decreased, is joint hypermobility. Joint hypermobility is usually caused by a congenitally softer type of connective tissue, making joint capsules, ligaments, and tendons less resistant to stretching. A recent paper estimated the prevalence of generalized joint hypermobility in a university-aged population as 12.5%, while a more severe form of hypermobility called Ehlers-Danlos may affect as many as 1 in 5,000. Stretchier tissues will lengthen father than stiffer ones before they are triggered to signal about lengthening, and this may contribute to the decreased proprioception in hypermobile individuals. An injury, such as an ankle sprain or ACL tear, may cause hypermobility or laxity in a single joint, causing the proprioceptive input from the injured joint to decrease, leading to instability in this but not other joints. Aging tends to decrease the input from the periphery, due to deterioration of mechanoreceptors, and perhaps in part due to age-related stiffening of connective tissue, and may also change how the brain processes incoming data. Older people tend to be much less physically active than younger people, and, especially in industrialized societies, loose joint flexibility and range of motion, causing poor communication about joint position for reasons opposite of that of the hypermobile. Inactivity decreases muscle strength, but in terms of balance and stability the effect of inactivity may be even more deleterious on the levels of the “software” of the brain, resulting in a decrease in the number of brain cells dedicated to propriocetive analysis and the previously mentioned motor programs. Short- and long term dangers of poor proprioception With laxity, injuries, inactivity and aging comes a different strategy for using the body. Instead of controlling joint movements in a skilled, precise way, we start to utilize stiffening strategies, which is like moving from the smooth, controlled movements of a jumping cat to the stiffer, wobbling of a duck. This stiffening, which means we are tightening muscles as if though walking on thin, slippery ice, is neither good for muscles, which start to ache and complain under the constant burden, nor is it healthy for our joints, which are not properly protected by these inferior strategies. With decreased proprioceptive prowess, decreased muscle strength, less effective stabilizing strategies and less impressive brain software comes an increased risk of acute falls and injuries, which can be devastating and present an enormous problem among the elderly. A decreased sense of joint position and movement can also lead to less stability of and a less precise use of joints. This, in turn, can lead to microtraumas, tiny but cumulative injuries, that wear out cartilage and keep muscles and ligaments in a perpetually irritated state, ligaments because of the painful pulling on them and muscles due to the resulting chronic, compensatory stiffness. Fear not, there is great news! So are the stretchy, the injured, and the aging among us doomed, (not to speak of those that are stretchy, injured and growing older)? As always, exercise to the rescue! With continued activity and exercise that challenges and strengthens our body we can all improve, sometimes tremendously so. Due to the incredible plasticity of our body, or the ability to continuously change in order to adapt to the demands placed upon it, we can all compensate for imperfection in one organ by improving another. The initial instability caused by a torn ligament, such as the ACL or MCL ligaments of the knee, can, through therapeutic exercise, be compensated for by increasing reliance on inputs from other tissues. The incredible muscle control of a classical dancer, who typically is quite hypermobile, is a beautiful demonstration of this ability to adapt and compensate trough continuous training and effort. The negative effects of aging are as much a correlation with increasing levels of inactivity as they are a result of inevitable aging-related changes in tissue. Regular physical exercise maintains the joint position sense, or the proprioceptive ability to feel our joints, of older individuals at near that of non-exercised younger individuals and more than twice as good as that of sedentary older individuals. As a matter of fact, the only strategy that seems to retain or help regain joint proprioception in older individuals is regular physical exercise. Positive effects of regular physical exercise on knee joint position sense (adapted from Ribeiro & Oliveira, 2010) Conclusion: start where you are, seek expert advice and keep going! So whether you have fallen prey to the myth that aging inevitably incapacitates you, or have lost the ability to move without pain in joints --unstable due to inborn laxity, accidents or both-- or whether you’ve been neglecting physical activity lately, or even always, there is a right place to start and much improvement to be had! Perhaps just as importantly, exercise of the right kind can be an invaluable tool for those with enough foresight to want to prevent injuries, whether due to the fact that they are hypermobile, new to exercise or are lucky enough to be getting older. No matter what the case may be, seeking the advice of a skilled physical therapist may make the difference between success and failure. Our bodies and brains are designed to survive in the moment and will always find a way to perform a movement, no matter how. This means that we almost inevitably end up with potentially harmful compensatory movement patterns. We wobble this way and that, overuse one muscle in order to not use another weak one, and rarely, if ever, find our way back to perfect, natural movement simply by engaging in a sport, a form of exercise, or dance. How we move is just as important as the movement itself, so seek the advice of a physical therapist familiar with your situation for guidance abut how to gradually, safely and effectively find the way back to the best version of you!

Pain exists for a reason. It is a warning sign that helps us protect our tissues. So shouldn’t we always heed the warning, and do everything in out power to avoid pain? The short answer is no, and this post is the longer, more detailed answer to that question, because pain is too important a phenomenon to misunderstand. Completely disregarding pain signals can lead to inappropriate movement patterns and habits, and subsequently to gradual, or even sudden, tissue breakdown. But being too avoidant of pain can lead to tissue weakness, deconditioning and decreased function. It can even shorten our lives. Sounds like a bit of a dilemma, doesn’t it? But it need not be, so let’s take a closer look. We have evolved for a lifestyle where pain co-exists with other drivers such as hunger or the need for social belonging and safety. If our prehistoric ancestors hurt their knee or their back a bit, they still had to keep moving in order to forage and hunt. The pain simply meant “move with awareness, maybe a bit slower or differently”. It did not mean “Stop!” Only the excruciating pain of a broken bone would have categorically stopped hunter-gatherers in their tracks. This balancing act helped them recover without weakness. Today we have high-tech imagery that shows what we are told is damage to our tissues, experts that give us ominous-sounding diagnoses for our ailments, and the ability to put dinner on the table without being physically active. This has gradually lead to a different interpretation of pain. Now virtually all pain seems to mean “stop”. This leads to lifestyle where we carefully avoid feeling more of it by moving less. Unfortunately, relating to pain in this manner can actually lead to the very thing we are trying to protect ourselves from, more pain and decreased function. Taking steps to avoid pain can sometimes lead to more, and chronic pain. But just like we use our intellect, instead of our hunger, to tell us when we should get some exercise these days, we can figure out when to move and when to stop even though circumstances don’t dictate the rules anymore. In order to do that we need to take a closer look at the various types of pain and what they mean. Pain can be divided into four types: nociceptive, peripheral neurogenic, central neurogenic and central sensitization. Peripheral neurogenic is nerve pain like the kind stemming from a pinched nerve. Central neurogenic pain stems from damage to the brain from an insult like a stroke, and central sensitization is an exaggeration of the type and intensity of a painful, and even non-painful, signal that can occur with chronic pain. I’ve written about that here. But most of the time what we’re feeling is musculoskeletal pain, ie the nociceptive type. This is pain stemming from tissue injury such as the pain that may occur after exercise or stubbing a toe, inflammation, pain from cramping, or other phenomena that lead to pain due to hypoxia, or insufficient oxygen in the tissue. Below is a chart where the various types of pain are organized according to my “traffic light system” that can help you decide how to related to a pain you’re feeling and know whether you should move or avoid movement. TRAFFIC LIGHT SYSTEM OF PAIN Red- severe, sharp pain that takes your breath away - Stop doing what you’re doing. Yellow- Some discomfort that doesn’t seem to get worse with what you’re doing - Keep moving, with awareness. Green- movement feels great, or is gradually decreasing the discomfort - Keep right on moving cap’n! Here are some examples of conditions where you might judge the pain you feel as either a green, yellow or red light: Green Yellow Red Muscle soreness from exercise, Soreness and pain in tissues such as A broken or se- stiff muscles, arthritic joints, ligaments and tendons that have very weakened been overloaded and hurt (tendonitis, bone or other plantar fasciosis etc), intense muscle conditions where cramps and spasm, healing tissues you’ve been told to absolutely Central sensitization avoid loading Central neurogenic pain the tissue for a while, recent surgery As you can see, pain should rarely be interpreted as an absolute ‘stop’. But, why not err on the side of caution and avoid the discomfort caused by movement when soreness or pain is present? Why, I thought you’d never ask! The reason we should always move if we can (no red light present) is that our bodies unequivocally need movement. That’s how they are designed. Movement adds forces to our tissues, signaling the need to build them stronger. Movement increases blood circulation, bringing oxygen and building blocks to tissues, helping them grow stronger and repair themselves after use or injury. Movement keeps our nervous system healthy and maintains our ability to feel, coordinate movement and balance. Any time we have to, or choose to, avoid movement, we are choosing not to have these phenomena benefit us, and unfortunately this causes our tissues gradually atrophy, or grow weaker. This makes us not just less able and strong, but also makes us more vulnerable and more at risk for injuries. Exercise also decreases pain by activating brain pathways that block pain signals, so suffering from pain should actually be a motivator for movement, not movement avoidance. Speaking of injuries, some of us don’t choose the too careful, pain-pain-avoidant path. They stubbornly keep charging ahead, and see pain as something of a personal offense, and pushing through the pain as a badge of honor. (You know who you are!) Remember the yellow light that means ‘move with awareness’? That also means intelligently changing the load on your tissues as needed, even as you keep moving. A runner whose hamstrings are hurting, and don’t get better with continued running, should of course address the reason for the pain, and during this process s/he will most likely benefit from some modification of their sport; running less or less often. Here the ‘awareness’ leads to change, being aware of what it is that is causing the pain and addressing the issue. (Hint: that most likely means a consultation with a physical therapist. These things can sometimes be hard to figure out on your own.) And speaking of yellow lights, there are many circumstances that should alert us to the need to ‘move with awareness’ and very gradually give out bodies the chance to grow stronger. If you are increasing your activity level, whether you are a seasoned runner who wants to increase your mileage or are starting an exercise routine for the very first time, give your tissues time to gradually get stronger. Connective tissue, which makes up most of what we are: bones, ligaments, tendons, skin etc, grows stronger much slower than muscles do. Don’t run ahead, literally or figuratively , and only follow the lead of your muscle strength. People with hypermobile joints, approximately 5-15% of the population, should also “start low and go slow” and give their weaker connective tissue a fair chance to grow stronger. If you are recovering from an injury, you are also rebuilding your tissues, so increase activity at an appropriate pace. So, when in doubt, move. Consult the traffic light system, decide whether yours is a green, yellow or red light, and keep moving. Get some movement every day, and more intense movement at least three times a week, and enjoy growing stronger! Link to my article about the connection between nutrition and health and recovery of the musculoskeletal system, posted at Physio Network.

|

Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed