|

Joint hypermobility disorders are actually body-wide disorders caused by alterations in connective tissue structure. For most individuals with a hypermobility disorder like EDS and HSD, some of the most noticeable and limiting symptoms are musculoskeletal. Not surprisingly, the diagnostic criteria of hEDS also center around musculoskeletal manifestations. Physical therapy (PT) is the most direct intervention, and therefore a logical choice for managing and improving musculoskeletal symptoms in hypermobility. It is the key to unlocking better health and function, while also empowering patients to understand and better manage their hypermobility in the long run. For some, however, the end result of a course of PT isn't quite what they expected or hoped for. This constitutes a truly unfortunate loss of opportunity, but some guidance can usually help us avoid a negative outcome. Let’s look at some of the reasons why PT doesn’t always lead to good results such as relief of pain, improved function etc, and more importantly, how we can maximize our chances of achieving our goals. And if you’ve fallen into any of these pitfalls, please don’t feel too bad. Even most healthcare professionals aren’t taught enough about hypermobility-related conditions to watch out for them. Ask yourself the following questions to see where and what you can change to maximize your odds of success!

If you can't find a hypermobility-savvy physical therapist in your geographical area, you can work with a therapist online, from the convenience of your home. This is probably a better idea than attempting rehab with an otherwise excellent PT, who may not be familiar with generalized joint hypermobility and your unique needs. 2. Are you moving too fast? Our bodies change at a certain rate, in part dependent on how closely we follow treatment recommendations, degree of hypermobility, starting point in rehab, our age, dietary quality, sleep quality etc. Make sure you’ve conquered one stage before you move onto the next. Skipping ahead may, like in a game of chutes and ladders, lead you right back to Start, instead of propelling you forward. 3. Are you doing enough? Most patients overestimate the speed at which their body can change, and underestimate the work it takes. I know, I, too, wish things would be a lot easier and more convenient! Look at it this way: In order to be – and remain! – healthy and functional and free of major injuries we all, hypermobile and “regular people” alike, have to be physically active enough on a regular enough basis. So whether you’re gradually climbing up your rehabilitative ladder, or staircase, if you will, you should be performing exercises on a daily basis, or at least moving daily and performing appropriate exercises on alternate days. The only difference is the exercises you are performing! 4. Speaking of staircases, are you progressing? A very common mistake is seeing the home exercises your PT gives you as a “one and done” set that you’ll be performing for a while, or perhaps indefinitely. Understand that your first exercises are only the very beginning. Our tissues grow, and our nervous system learns, gradually, not overnight, and one function in our body depends on the proper functioning of another. Because of this, PT should instead be understood as a gradual progression towards your ultimate goal, where you move from one level of difficulty to the next. An analogy would be school, where you are moving from one grade to another based on the completion of each grade level. You could also see it as a gradual climb up a staircase. You neither want to stay stuck on the lower steps, nor try to skip steps and risk tripping and falling down to the bottom of the stairs. 5. Did you take your exercise medicine as prescribed? Just like prescription medication, the therapeutic exercises your PT gives you are prescribed precisely in regards to type, load, frequency etc. Engaging in what I jokingly call “a la carte PT” –- picking and choosing among your exercises and performing each individual exercise irregularly instead of with the recommended frequency -– will dilute the effects of each exercise, and keep you from achieving your goals. Remember, each exercise has a very specific goal, and performing it as prescribed is important. 6. Did you give up? One of the most common and also most fateful PT mistakes is giving up. Believe it or not, the majority of people do not complete their PT. They expect changes to be rapid, and have a hard time sticking to a regular routine of performing exercises. Again, the body changes at a slow pace, and the first improvements you should expect to see are not typically pain relief, but a gradually increasing ease of performing your exercises. Pain is the body’s voice, and it is asking us to change something. Until we have corrected whatever the body’s symptoms are "talking" to us about, we should not expect to be pain free, but instead, as surprising as this may sound, even be a little grateful that the body does have a way of telling us about malfunctioning, so that we have a chance to institute changes before it’s too late. 7. Do you believe in “no pain no gain”? A common belief is that PT has to hurt. But the body is not an adversary to be conquered, but a friend in need. As a matter of fact, it is a friend that has faithfully served us, despite suffering from various problems. One of the first things I tell my patients is that no exercise I give them should hurt, neither while you're performing it, nor afterwards. A typical patient with a hypermobility condition enters into PT with a lot of tension, apprehension, dissociation (“tuning out” of the body in whole or in part), stuck in some degree of sympathetic nervous system overdrive (“fight or flight”), with a limited belief in his/her body’s ability to change, and with lots of habits and movement patterns that work against long-term goals. As you can see, there’s a lot that needs to change. But that also means that there is a lot of opportunity and a lot of room for improvement! 8. Are you conflating 'exercise' with 'workouts'? This is another very common obstacle to success. Conflating these two concepts leads some to feel that they must "work out" to get better, no matter how much it hurts, and makes others avoid all forms of exercise, even appropriate ones, at their own peril, because they've been warned not to work out. When symptoms are prohibitive, working out in the traditional sense may indeed not be a good idea. But the concept of exercise is actually a very wide umbrella under which we sort everything from the most strenuous workouts to the most gentle forms of muscle isolation, breathing techniques, gentle stretching etc. Therapeutic exercises can be adapted to any situation, need and condition, and gradually progressed as appropriate, and this is usually where the symptomatic hypermobile patient should start. While some may feel some resistance when getting started with, and specially sticking to, a rehabilitative program, things do get a lot easier once you've created a habit of adhering to your program. Research shows that repeatedly choosing to do something because it is the right choice, even though we might not quite feel like doing it, actually strengthens the part of the brain connected to willpower (1). The power of habits is a very helpful ally! Envisioning your long-term goals, remembering why you are doing this, and focusing on feeling gratitude for the fact that you actually can effect change, can also be very helpful. None of us know what our maximum capacity actually is, and most of us underestimate it. We should therefore be careful not to set any artificial limits for our improvement. Sometimes the official diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or another hypermobility-related condition feels like such welcome validation and a relief (“I’m not an anxious malingerer after all, like I’ve been told!”) that we risk falling into a set, predetermined role that may include unnecessary limitations. Dare instead to dream a little, aim for a body that functions and feels better, but dream like a turtle, of gradual, thoughtful progress. After all, as the parable tells us, this is the way to win the race! 1) Torotoglou et al. The tenacious brain: How the anterior mid-cingulate contributes to achieving goals. Cortex. 2020.

0 Comments

Pain is one of the main symptoms that people with hypermobility report, and seek treatment for, but it may be one of the most difficult symptoms to understand. What’s to understand about pain, you say. You either hurt or you don’t, right? Pain is actually a very complex phenomenon, and just like when baking a cake, the end result depends on all the ingredients and how they are combined, and what we do with them. Because the issue is complex, I won’t try to cover it in its entirety, but rather give you some general sense of the landscape of pain. The main take-away is that pain is a complex phenomenon that is the end result of a variety of factors, some of which can be modulated more easily than others. Pain is highly modifiable by many psychological factors, including expectations, our perception of how safe (or not) we are, how we think about pain, whether we tend to catastrophize or not, whether we have an internal locus of control – a sense that we ourselves can have an impact on our pain – and a multitude of other factors. What pain is not: an accurate measure of the degree of tissue damage or dysfunction in the body. Pain is not an accurate measure of the degree of tissue damage or dysfunction in the body. Contrary to what it may seem like we experience pain in our brains, not in the part that appears to hurt. Whether we experience a stimulus as painful, what type of pain we feel, and how intense the pain feels depends on the brain’s interpretation of what the stimulus means, of how threatening to our safety and survival our brain believes the sensation is. This means that pain depends on our perception of the stimulus. Our perception in turn is affected by our previous experiences. Stating that pain is modifiable does not mean that if you just thought better thoughts, you wouldn’t be experiencing it. It simply means that we have some control over our experience, and with time, can learn to exert even greater control over it. Polyvagal theory The psychiatrist Steven Porges, PhD, has developed a theory called The Polyvagal Theory that further specifies the function of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in different emotional states, specifically in states of safety or lack of safety. It serves as a helpful way to understand the way we connect and bond, and how we react when we are not feeling safe. It further divides the anatomy and functioning of the vagus nerve into two branches, the ventral (meaning anterior) and dorsal (meaning posterior, or towards the back) branches of the nerve. The theory states that when we perceive signals of safety from others, we are open to connection. When we feel threatened, we first go into sympathetic nervous system (SNS) mode, commonly known as “fight or flight”, and if this is not possible -- we are immobilized in a threatening situation, see no way out -- we may move into the dorsal vagal state, commonly known as “freeze”, characterized as giving up, passivity, indifference. Polyvagal theory can both be helpful to our understanding of how traumatic experiences and a lack of a sense of safety in our bodies and the world affect us, and a helpful tool in supporting more calm and connected states that favor tissue repair and lowered pain responses. Central sensitization - the unkind magnifying glass of sensation Pain can both be amplified and dampened by a variety of factors. Fear, fear of movement, a sense of not being safe, catastrophizing, an external locus of control (a belief that factors outside of oneself hold all the power over one’s well being), high levels of inflammation in the body etc. can all ramp up the pain. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as well as trauma during adulthood can contribute to a decreased resistance to stressful events, an enhanced risk of sensitivity to pain and central sensitization of pain. This happens in part due to the potential of traumatic experiences to induce lasting effects on the structure and function of stress-regulating circuits in the brain, such as the hippocampus and the amygdala. This can promote alterations in stress and pain sensitivity and regulation of emotions in later life. People with a history of trauma exposure may have decreased volume in the frontal lobe of the brain, affecting executive function. In addition, they show a wider pattern of increased pain sensitivity that even includes parts of the body other than the most problematic area. In some cases Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) symptoms appear to have emerged or worsened after physical trauma. In some studies brain changes have through visual imaging been linked to the emergence of physical symptoms. People with EDS have also been found to have alterations in the size of key emotion-processing brain regions, such as the amygdala. Elevated levels of stress also contribute to elevated levels of inflammation,, leading to more pain through the release of so called pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemical messengers that signal and prompt inflammation. (Pro-inflammatory cytokines can also be released due to infection or injury to cells.) Fear of pain itself has been found to increase the risk of the pain becoming significant and chronic. Pain-related fear and avoidance of movements and activities we mentally associate with pain, no matter how understandable they may be, have been shown to make matters worse, leading to more severe disability progression of disability over time. Fortunately, the opposite spectrum of emotional states -- feeling safe, supported, informed, in control, having low levels of inflammation -- can contribute to a decreased perception of pain. The vagus nerve, the main branch of which is associated with the relaxed states of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), inhibits oxidative stress, inflammation and the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. Despite the fact that pain isn’t always accurate and exact in terms of how well it can tell us where a problem is located, and how severe it is, it still has an important signaling function. In cases where the pain is chronic –- has lasted over 3-6 months –- a phenomenon referred to as central sensitization can increase a person’s perceived levels of pain due to changes in the central nervous system itself. This increase in pain does not reflect increased dysfunction in the parts of the body that hurt, but is a dysfunctional, unhelpful phenomenon, a problem in and of itself that requires specific treatment. When this sensitization is to pain in the musculoskeletal system, it is often diagnosed as fibromyalgia. This also explains why so many individuals with hypermobility disorders have received this label prior to being diagnosed with a form of EDS or Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD). In a 2016 study of 27 patients with joint hypermobilty the participants were found to have widespread pain but no peripheral nervous system damage. There were, however, findings compatible with central sensitization. The researchers concluded that in patients with EDS or HSD the ongoing pain due to joint abnormalities probably triggers central sensitization and causes widespread pain. Central sensitization is a “re-wiring” of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) that reflects a persistent state of high reactivity that lowers the pain threshold. It either leads to greater suffering from an ongoing condition or dysfunction, or maintains pain after the initial cause of the pain no longer exists. Please note that there is a difference between the concepts of pain threshold, the minimum level of stimulus that is perceived as painful, and pain tolerance, referring to the amount of pain an individual tolerates. You can both have a high pain tolerance – tolerate a lot of pain and still function – and a low pain threshold – feel pain with a lower intensity of stimulation than average. Both are to some extent malleable, and can also vary due to previous experiences, such as trauma, or genetics. As mentioned, pain can also be influenced positively or negatively by a variety of other factors. Keeping these in mind as you work on your rehabilitation can be very helpful. You can both have a high pain tolerance – tolerate a lot of pain and still function – and a low pain threshold – feel pain with a lower intensity of stimulation than average. One does not exclude the other. Pain and rehabilitation How should we take pain into account during physical rehabilitation/physical therapy of a hypermobile person, who is likely to be sensitized to pain? Therapy itself should (in all but some very specific cases) not increase pain in the moment. You should also not experience pain as a result of having performed therapeutic exercises, received a manual treatment intervention, or made recommended lifestyle changes. If you experience pain while performing a therapeutic exercise –- a common experience of many hypermobile patients that have sought help through physical therapy, only to find that it instead aggravated their symptoms –- you are performing the exercise incorrectly either because you are not yet ready for it, or have misunderstood it. The “not yet ready for it” is a likely and common reason for physical therapy fails. Hypermobile individuals are often prescribed exercises for which they are not yet ready. In either case a course correction is in order, and pressing ahead would be a potential recipe for injury or pain aggravation. When an exercise causes pain we should, however, not recoil from it, but rather find the best way to proceed without pain. When an exercise causes pain we should, however, not recoil from exercise , but rather find the best way to proceed without pain. While the goal of physical therapy should generally not be pain relief at the moment, it should eventually help decrease pain. It does this by gradually normalizing the body’s functioning, which then results in pain relief, and even freedom from pain, because there simply is no injury or dysfunction for the body to signal through pain. But since the intrinsic function of pain is to keep us safe by warning us against danger to our bodily integrity, physical therapy must also proceed in a way that makes us feel safe. This includes not only educational components that help the patient distinguish signs of danger from the sensory background noise of embodied existence, but also an approach that doesn’t itself add to the sensitization and the experience of movement equalling pain. When the weak links have been strengthened, the bugs in our movement software sorted out and our tissues are animated by a brain that feels safe, movement, whatever form it takes for each individual, is not only a pleasure but a necessary vehicle for experiencing any and all of the experiences life has in store for us. References: Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009 Lucchetti et al. Anxiety and fear-avoidance in musculoskeletal pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 201 Luque-Suarez et al. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019 McKernan et al. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Mediate the Effects of Trauma Exposure on Clinical Indicators of Central Sensitization in Patients With Chronic Pain. Clin J Pain. 2019 Herzog et al.Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Consequences on Neurobiological, Psychosocial, and Somatic Conditions Across the Lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Fleming et al. Central sensitization syndrome and the initial evaluation of a patient with fibromyalgia: a review. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2015 Giotakos O. Neurobiology of emotional trauma. Psychiatriki. 2020 Simon et al. Pain catastrophizing, pain sensitivity and fear of pain are associated with early life environmental unpredictability: a path model approach. BMC Psychol. 2022 Hamonet et al. Brain injury unmasking Ehlers-Danlos syndromes after trauma: the fiber print. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016. Eccles et al.Brain structure and joint hypermobility: Relevance to the expression of psychiatric symptoms. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6) Bulbena et al. Psychiatric and psychological aspects in the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017 Maes et al. The effects of psychological stress on humans: Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a Th1-like response in stress-induced anxiety. Cytokine. 1998 Jankord et al.Limbic regulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical function during acute and chronic stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Zhang et al. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007 Markfelder et al. Fear of pain and pain intensity: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychol Bull. 2020 Gidron et al. The Vagus Nerve Can Predict and Possibly Modulate Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases: Introducing a Neuroimmunological Paradigm to Public Health. J Clin Med. 2018 Oct Di Stefano et al Central sensitization as the mechanism underlying pain in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. Eur J Pain. 2016. Congratulations! You’ve chosen to start physical therapy, the most effective way of addressing hypermobility - related musculoskeletal concerns and symptoms in individuals with hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS). Please take the following suggestions to heart in order to maximize the benefit of your therapy, prevent future problems and help you achieve your highest possible level of function.

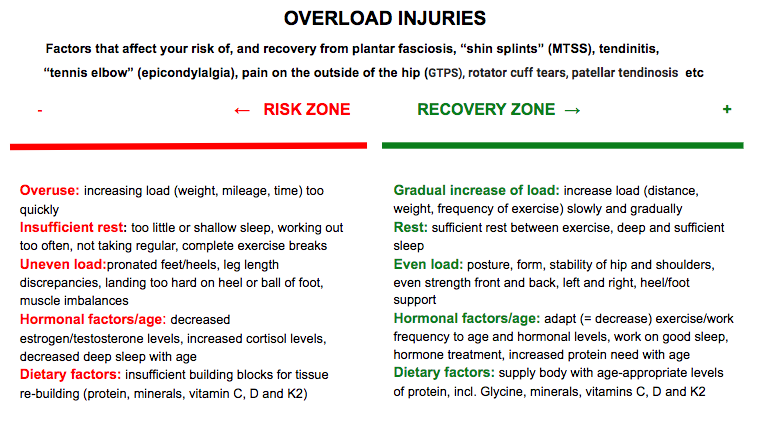

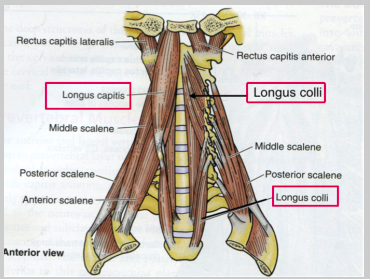

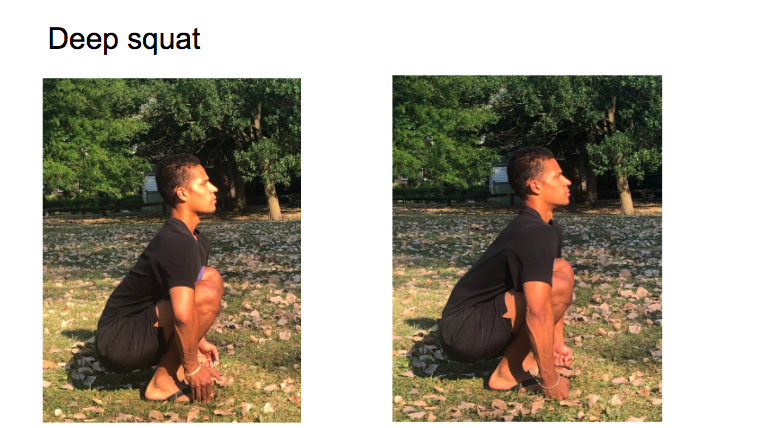

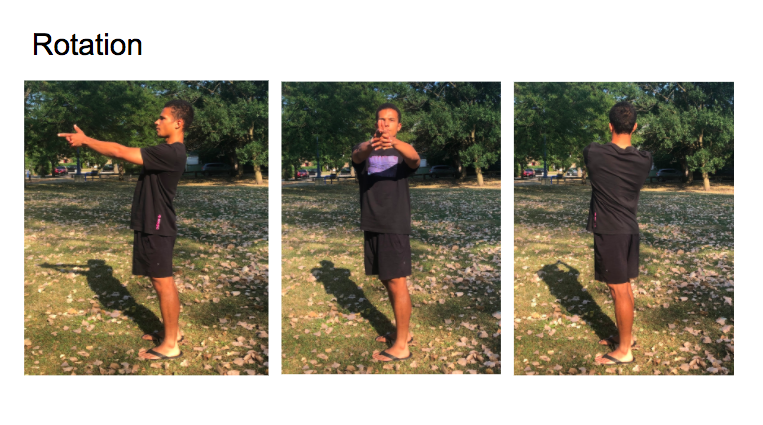

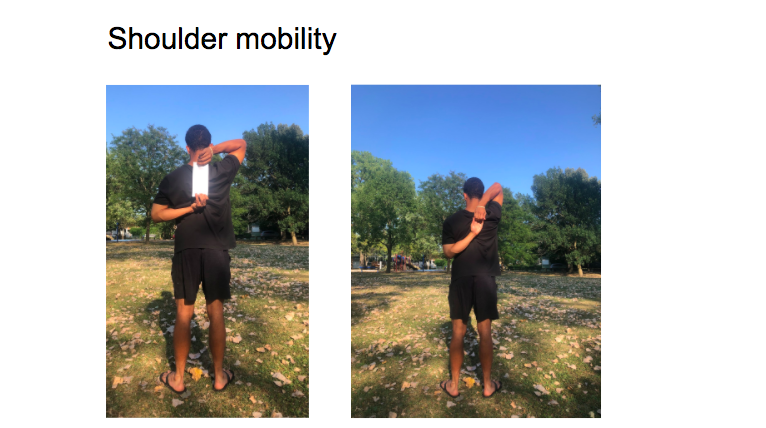

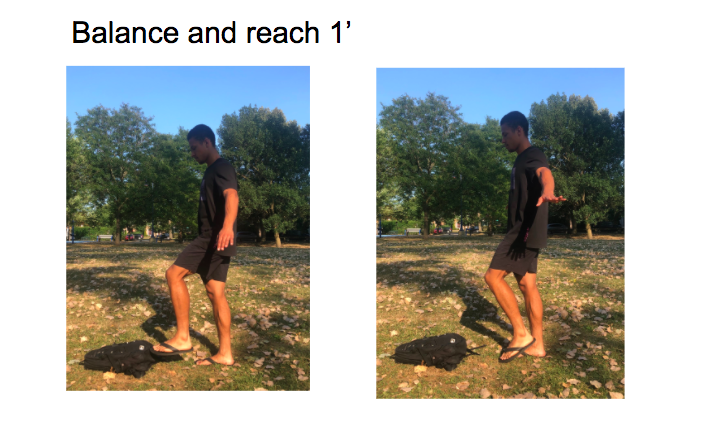

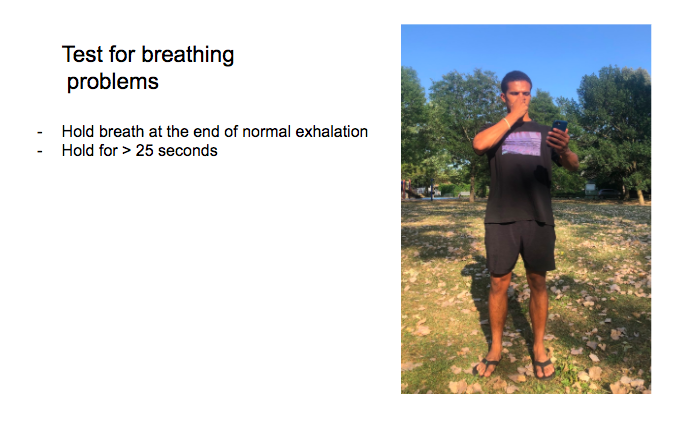

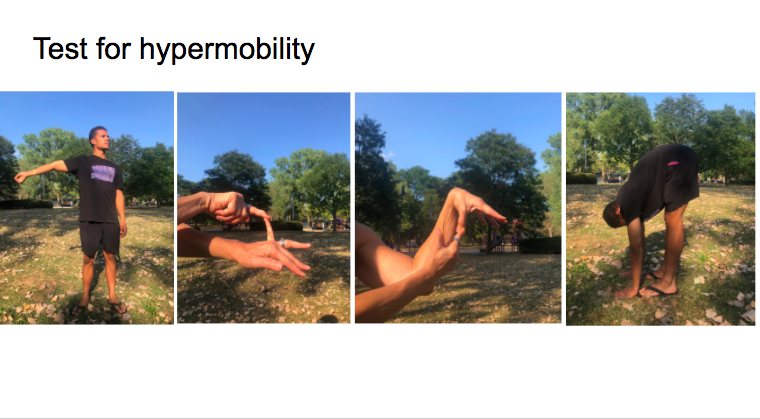

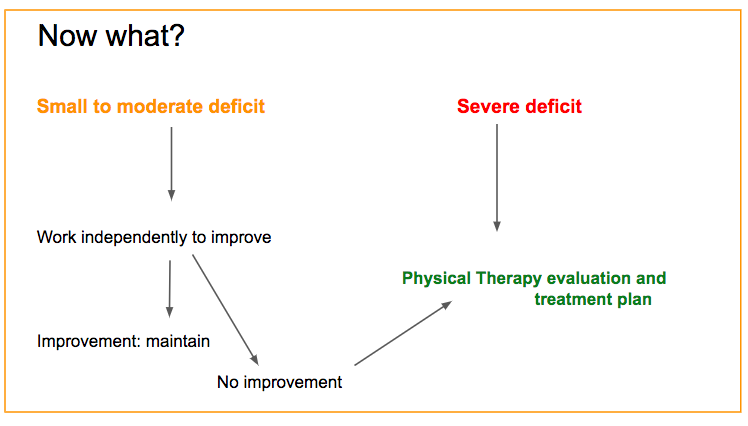

You know exercise is good for you, but what if it causes pain and soreness? People with hypermobility disorders benefit from exercise even more than others, but exercise also presents some additional challenges for their inherently less stable bodies. Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD) and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) are conditions caused by a disorder of collagen biosynthesis and structure that cause the connective tissue in hypermobile bodies to possess less stiffness than normal connective tissue. This, both directly and indirectly, makes people with HSD and EDS more prone to musculoskeletal injuries. Injuries may be micro-injuries, i.e. microscopic injuries that tend to accumulate over time resulting in “wear and tear” on tissue and manifest as osteoarthritis, tendinosis and other forms of tissue breakdown. They may also be macro-injuries which, as the name implies, are frank injuries to tissue, such as a tear of a ligament or tendon, or fracture of a bone. There is also a grey area between the two, where gradual imperceptible changes in tissues cause findings that are often perceived as macro-injuries, as in rotator cuff tears and bulging discs. Remember that exercise in and of itself, strictly speaking, strengthens muscle by causing “injury”, small micro-tears in muscle tissues. As these heal in the days following the exercise, the muscle builds itself back stronger than before in response to the load imposed on it. This process is completely natural and benign in the non-hypermobile body. Decreased joint stability and decreased tissue strength coupled with slower healing of tissue can make hypermobile people more susceptible to increased exercise-related soreness and pain. This is unfortunate, as hypermobile individuals may, if deterred by their experience, suffer more significant consequences of a sedentary lifestyle than their friends and partners with connective tissue of normal strength. In order to make it possible for hypermobile individuals to enjoy the many benefits of regular exercise, the exercise prescription for the individuals with HSD/EDS requires a thoughtful and gradual approach. Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is a phenomenon which, while not yet fully understood, is considered normal, and tends to occur after exercise. It is especially likely when the exercise is intense, new, increased in load, duration or intensity or contains an eccentric component (muscle contraction during the muscle lengthening phase, as in walking or running down a hill, or slowly lowering a weight). Various phenomena such as lactic acid, muscle spasm, connective tissue damage, muscle damage, inflammation and the enzyme efflux theories have been proposed as underlying mechanisms, and in all likelihood DOMS may occur as a combination of any and all phenomena. When the hypermobile person experiences soreness or pain following exercise, it can be hard to distinguish between the more benign DOMS -- which, as mentioned, due to several factors may feel more intense in hypermobile individuals -- and actual injury to tissues, the latter of course requiring more attention and prevention than the former. So how do you distinguish DOMS from injuries that you should be concerned about? DOMS tends to be more generalized, including muscles which may be sore both on movement and palpation. An injury to a joint or muscle is more often one-sided and more localized, and the pain may prevent movement in a more specific direction. For example, having exercised or in other ways been physically active in a way that included use of the arms may make you sore in the arms and shoulders in general. An injury --again, here we are excluding the benign microtrauma that beneficial exercise causes, even though it technically speaking is an “injury”-- to the shoulder joint may, as an example, present as pain with moving the arm upward or behind the body, but feel much better with the arm lowered and at rest. Another clue is the timeframe. DOMS usually eases within 2-4 days, having appeared with some delay, whereas an actual injury will still be present after a few days. Preparation is protective Problems are best prevented, of course, and pain and soreness due to exercise is no exception. Exercise is one of the best treatments for the various manifestations of hypermobility, and problems associated with hypermobility are best addressed holistically, taking the entire body of the person into account, instead of addressing injuries one by one, as they occur.While high-quality studies on the effect of physical therapy on hypermobility conditions such as HSD and EDS are lacking we can extrapolate from what we know about rehabilitation of acquired hypermobility in single joints, and on the smaller studies that do exist, and conclude that over time, the decreased joint stability can be improved with training, and even decreased strength of muscles and tendons can be positively affected by the mechanical loads provided by regular exercise. There are several factors we can take into account before exercising that can decrease the risk or intensity of DOMS and injury-related pain. When planning to start a new type of activity, it's best to first analyze -- usually with expert help -- what the requirements are for safely performing the activity in question. As an example, if you'd like to be able to walk, run, zumba or dance for exercise, you will need trunk stability, hip strength and stability, a full range of motion especially in your hips and your big toe, and good foot strength and movement form. All of these can be acquired prior to starting the desired form of exercise. A would-be runner or dancer could engage in a lighter version of the activity -- walking or working on slow dance steps -- while working to improve the aforementioned basic requirements for safely performing the activity. A common mistake is to assume that the activity itself will help you develop the requisite stability, mobility and strength needed for this. There are two problems inherent in this assumption. First, what will protect you during your exercise until you have acquired these skills? Second, this expectation is based on the somewhat faulty assumption that the body during movement will recruit weak muscles to perform the activity, when stronger muscles are available to compensate. Think of the body more as a survival machine than a self-rehabilitating organism. We are much more likely to instead develop compensatory movement patterns that in the long run lead to subpar performance and even pain and injury, than to spontaneously develop good, balanced strength and perfect form while performing a new activity. This makes perfect evolutionary sense. What would have been a greater priority to our ancient forebears, running away from the risk of becoming someone’s next meal as fast as possible, even though some injury might have left us with decreased strength in some area, or jog away a bit more slowly using all muscles ideally needed for the escape, including weak ones to make sure that (in the unlikely event that we survived using this strategy) we would once again develop a balanced body? Keep in mind the time it takes (usually longer than normal in hypermobile people) for your body to respond to exercise and to progress. Do your best to add load very slowly when you’re challenging your body to grow, allowing it to respond fully to the previous level of exercise before you progress. One factor that may lead us to try to progress faster than we should is the fact that the exercise itself decreases the perception of pain during the activity. This phenomenon is referred to as exercise-induced hypoalgesia. While this mechanism may be reduced or altered in chronic pain, a single bout of aerobic or resistance exercise typically leads to a generalized reduction in pain and pain sensitivity that occurs during the exercise itself and for some time afterward, so that you may feel fine while exercising, only to realize afterwards that you exposed your body to too much, too soon. When in pain… Once exercise soreness has set in, there are still things you can do to improve the situation. While pain can feel scary, and while you might, understandably, want to avoid the very thing that brought it on, the best strategy is to avoid complete physical inactivity. Try to remain physically active, but with a much lesser intensity and duration. A short walk can ease the sensation of stiffness and soreness along with the regret of having overestimated your capability. Cooling nerves slows their conduction velocity (the speed at which they send signals to the brain) so applying a cold pack can decrease pain significantly. Apply it over a damp washcloth to any area that hurts, for 20 minutes at a time. Allow the skin to return to a normal temperature before reapplying in order to avoid frostbite. Icing will, however, not positively affect the rate at which you heal, and you actually do not need to do anything to make DOMS subside, as it is a natural phenomenon and will pass on its own. There is also some data suggesting that gentle stretching can modulate the inflammation causing the pain and stiffness. Remember that in this context stretching means coaxing muscles to relax, not forcing them to lengthen. While you’re feeling sore you can still exercise other parts of the body than the involved ones. If you suspect actual injury, you should of course seek help. If you're simply experiencing DOMS (delayed-onset muscle soreness) gentle movement is helpful. Pain intensity is affected by our beliefs and this means that how you perceive pain affects how much you suffer from it. Reminding yourself of the fact that exercise soreness is a natural, benign and self-limiting phenomenon helps alleviate any concerns that you may have and will make it more likely that you’ll sail through DOMS without suffering needlessly. Since hypermobility may lead to greater than average exercise-induced soreness, as well as slower post-exercise recovery, it is also important to gauge whether the intensity of the soreness is greater than ideal. When in doubt, in the presence of HSD/EDS it is usually a better idea to progress slowly and carefully in order to avoid the dreaded boom and bust- phenomenon; advancing too quickly only to be sidelined by an injury. With hypermobility, impatience is the enemy of progress, and patience is your secret superpower!  Once upon a time, it was widely believed that the sun orbited the earth, and not the other way around. This was a perfectly logical assumption, since that is what it looks like from our vantage point on Earth. It is also a good example of the fact that, sometimes, assumptions that seem perfectly logical can actually be wrong. The experience of pain, and the assumptions we make based on it, can often fall into this category. When you feel a sharp pain in your back, it is easy to make two assumptions: something in the back must be injured, and the safest thing to do must be to stay still. In most cases, both assumptions are incorrect. Why does this even matter? Whether right or wrong, you’re still in pain. The reason it matters is that understanding what is going on “under the hood” helps you take the appropriate steps to feel better, whereas operating under a false assumption can lead to more, and even chronic, pain. The scientific term for believing that we are vulnerable and should avoid movement to protect ourselves from further injury is Fear Avoidance Beliefs .These beliefs have been shown to be strongly correlated with the transition from acute to chronic pain, and can therefore literally be hazardous to our health. A functional model of pain The view of the body as consisting of separate parts that malfunction, predictably cause pain when they do, and, in order for pain relief to be possible, should be exchanged or repaired like car parts, is called the biomedical model. This model is considered a bit outdated, and has been replaced with the biopsychosocial model of pain, which takes several other relevant factors into account. Pain can of course be caused by tissues that are ailing, but it can also be decreased or increased through independent functions of the nervous system, even without any physical damage being present at all. This is termed neurogenic pain. Our beliefs, fears and other psychological factors can also turn the volume of the pain signal up or down. The pain caused by tissues that are being irritated, inflamed etc is termed nociceptive pain . Sometimes this is indeed caused by something breaking or wearing down, and even exercise soreness is, on a microscopic level, happening due to inflammation caused by small tissue fibers breaking during a workout. While this may sound like a bad thing, it is actually the first step in a chain of events that lead to muscles growing stronger. In the majority of cases, however, the solution to musculoskeletal pain isn’t waiting passively for tissues to heal while avoiding movement, and in cases of chronic pain this is even easier to understand - if waiting for healing would have helped, you’d be healed by now. So why are you hurting, chronically or often? More often than not, the underlying cause is to be found not in whether the tissues are broken or not, but in how they work together. Knee pain is a common complaint, and when certain movements cause a sharp pain behind the kneecap, it’s easy to understand that the instinct may be to minimize or avoid movement of the leg altogether due to fear that something must be damaged, and more movement may damage it even more. But the truth may be that the pain, or dislocation, if that is the chronic concern, is happening due to hip or buttock muscles not working correctly and failing to stabilize the thigh bone, which in turn makes the kneecap move incorrectly in it’s groove. The solution to this dilemma is education and exercise, not inactivity. While it may seem like a good short-term solution, avoidance of movement will soon result in ever weaker muscles and more pain. This functional lens can help with pain anywhere in the musculoskeletal system. Back pain? More often than not muscles triggered into a spasm due to insufficient muscular stabilization of the spine. Shoulder pain? Maybe your humerus, or upper arm bone, is not moving correctly in it’s joint due to weak rotator cuff muscles and poor positioning of the shoulder. When we start to understand that the various component parts of the body not only need to be healthy but also need to work together, as a system, it makes sense that pain can arise as a result of a system failure, and that, through appropriate and specific exercise, training the system to work correctly is the solution. Studies show that wear and tear of tissues is predictable and increases steadily by every decade of life, but this wear and tear correlates very poorly with pain. In other words, you may have significant degenerative changes in any given body part without any pain at all, and intense pain is often experienced in parts of the body that look fine on x-rays and MRIs. This does not, however, mean that pain should be disregarded as something to be pushed through or walked off. Exercise should never hurt, and pain is always a signal -- we just need to interpret it correctly. A skilled physical therapist can help you by evaluating you and guiding you through a gradual progression of exercises that will, when appropriate, normalize the functioning of your body to first eliminate and then prevent pain. The hypermobile body heals more slowly than other bodies, and strength gains also take longer to become apparent. This calls for both persistent adherence to the exercise program and a lot of patience, but the rewards are always worth the effort. Avoidance of movement can only lead to an ever-shrinking tolerance and ability, and if you paint yourself into too small a corner it may be hard to reverse the dysfunction. Let your body -- slowly but surely-- surprise you. You may be able to feel and function much better than you ever believed you could. What’s the worst thing that could happen? Preventing an otherwise predictable, slow decline, and that’s a worthy goal in and of itself!  Are you, or were you once, much more flexible than most people, or do you know someone that is? The flexibility may be a sign of hypermobility, or joint hypermobility, a term that refers to joints that move beyond their normal, or average range. The current terminology for hypermobility that leads to symptoms such as pain or joint injuries is hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) or, if certain diagnostic criteria are met, hypermobile Ehler-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS). HSD and hEDS are, according to many experts, simply different points on a broad spectrum of hypermobility. The joint hypermobility is believed to be caused by genetic variants, (the types of which are at this point still unknown, and probably vary from person to person) in genes affecting collagen, making it less strong. Collagen is the main structural protein of connective tissue and is therefore an important component of tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, skin, bone, the fascial tissue in and around muscles and other organs etc. Connective tissue is also an important component of all the organs in the body and hypermobility therefore usually affects a variety of bodily functions in addition to its effects on the musculoskeletal system. While the hypermobility itself is more pronounced in youth, the symptoms it causes often become more apparent over time. The flexibility that once helped with dance, gymnastics or yoga may decrease, and be replaced by the joint laxity that brings on headaches and joint pain. This can lead to a downward spiral of pain and decreased physical activity. Decreased physical activity leads to weakness and further loss of stability, leaving the hypermobile joints unprotected and at risk for both acute and gradually progressing injuries. The way out of this downward spiral is correcting the weakness and lack of stability while progressively and safely increasing the amount of physical activity, utilizing principles based on an understanding of the unique needs of the hypermobile body. Basic principles for physical therapy for the hypermobile body Since in joint hypermobility, HSD and/or hEDS, joint structures such as joint capsules, ligaments and tendons acting on the joint tend to possess less stiffness, i.e. be looser, compensating for this looseness with appropriate muscle function is important. Raw strength may not be the best thing to focus on initially, but rather motor control, the control of your muscles by your nervous system. Stability is a key concept in rehabilitation of the hypermobile body. We want muscles to function effectively to prevent too much, or the wrong kind of, movement in the joints. The goal is, first, a trunk that is stable, controlled and possesses endurance. In other words, you want your trunk, from the pelvis to the neck, to be able to remain relatively stable -- but not stiff-- while your extremities move. When walking or running, the trunk does rotate a bit, but the bulk of the movement should happen in the lower extremity joints-- the hips, the knees, ankles and feet. When lifting something overhead, the movement should happen from the shoulders, instead of being achieved by arching the low back. Upon this stable trunk the shoulders and the hips control the movement of the arms and the legs. These joints also require a lot of stabilization, the work of certain muscles to guide the movement of the limbs in a stable and effective way, while keeping the joints in place, preventing subluxations and dislocations. Stabilization is a complex process which, depending on the amount and type of movement, is the end result of the nervous system functioning correctly and muscles possessing the requisite amount of strength and endurance. To (over)simplify this process a bit, think of your muscles as being able to provide either stability (the selective prevention of movement) or movement. There is a lot of overlap, but some muscles work primarily in a stabilizing function, while others work primarily as prime movers, creating movement. The stabilizers tend to be made up of muscle fibers, so called slow twitch fibers, that are weaker but possess great endurance, whereas the movement-producing muscles (fast twitch) possess greater strength but fatigue faster. This is why stabilizing exercises don’t tend to make you huff and puff, but are focused on controlling the body against gravity or movement. Do not, however, underestimate their power and importance! They may not always make you sweat, but they are the kind of exercise that stands between you and acute back spasms, subluxations and gradual degenerative injuries of your body. A very important additional effect of the exercise that rehabilitation includes is the stiffening and thereby strengthening of the softer ligaments and tendons.This directly and positively affects the ability of muscles to control joints and movement more effectively. Patience and gradual progress The various tissues of the human movement system all respond to exercise and strain, but they don’t develop at the same pace. Muscles grow bigger and stronger faster than your ligaments and tendons grow thicker and stronger. “Start low and go slow” is an oft’ repeated mantra that holds a lot of truth for individuals with HSD and hEDS. The softer connective tissue structures may actually make the individual a bit more susceptible to the naturally occurring delayed-onset muscle soreness that occurs after heavy exercise. The body repairs this micro-damage primarily during deep sleep, and since hypermobile individuals often have disrupted sleep, the repair process may be slower. The instability that may occur during movement may also increase post-exercise soreness. Expect to progress in a slow, methodical fashion. Take a step back whenever you notice any signs (fatigue, soreness, weakness, pain) that you may have been overly enthusiastic. You will eventually achieve your goal, but you can’t change the fact that it’s going to take a certain amount of time. Impatience is your enemy here, and “slow and steady” should be your mantra. Remember not to add resistance or speed until you have achieved stability! Physical therapy should not be reactive, but proactive and constructive While physical therapists have many tools in their toolbox to help with acute pain, the best use of physical therapy isn’t seeing a therapist for relief of acute pain (being reactive), but for the gradual correction of any deficits, imbalances and other problems that lead to pain in the first place (being proactive and constructive). The acute pain, if not addressed at its root cause, will come back, and over time worsen. Better to work on stability, balance, coordination, motor control and strength etc, in order to protect the body from both acute and gradual injuries. This way future occurrences of pain may be prevented, or at least decreased. You may also be able to safely move on to other types of movement, if basic strengthening and cardiovascular training doesn't appeal to you as a long-term strategy for keeping your body stable and healthy. Moving directly to other forms of movement, be they running or pilates or anything in between, may not, however, be such a good idea, as unprepared, our bodies tend to stick to their compensatory (incorrect, unhealthy) movement patterns instead of correcting themselves. Our bodies are survival machines, and will always use the strongest muscle at their disposal, and the easiest way of doing something, instead of using the weak or underactive muscles that should be learning to perform it. Being able to do something doesn’t necessarily mean that you are doing it in the way nature intended, and you may unknowingly be hurting yourself. Whether a dancer or a runner, you may be moving too much in your low back and not enough from your hips, or compensating with one muscle, for another, weakened one, and overloading the compensating areas. Yes, it is a bit complicated If all this sounds a bit complicated, it’s because it is. You need to have some understanding of both your unique, hypermobile body as well as the rehabilitative process and its principles. You need to be able to know where to start and how to progress, how to problem solve and how to adapt your exercise program to your unique needs and goals. In order to achieve your goals, you should ideally be working with a doctor of physical therapy (DPT) with experience with hypermobility. As is the case with all healthcare professionals, physical therapists don’t tend to receive much training in the management of hypermobility disorders during their educational process. Whether you’re looking for a medical doctor or a doctor of physical therapy, make sure that the practitioner you’ll be working with is experienced in treating bodies like yours. The good news is that hypermobility responds very well to rehabilitation. As a matter of fact, hypermobile individuals both benefit more from and need (specific) exercise more than other people, and it’s a medicine with only good side-effects!  Isolating yourself physically in order to avoid COVID-19 is necessary from an epidemiological standpoint, but for your overall health, it can be detrimental. As we have isolated ourselves at home, avoiding workplaces, gyms and even grocery stores, both the amount and variety of movement we engage in on a daily basis has, for most, decreased significantly. The small muscles close to your spine, from your low back to your neck, weaken quickly when we spend a lot of time sitting with a backrest. When these muscles don’t stabilize the bones of your spine properly, then fatigue, pain and gradual degenerative changes follow. When bigger muscles remain underutilized, they shrink and weaken, too. But did you know that this not only leads to weakness, but also to problems regulating blood sugar, difficulties with balance, body composition and an increased risk for everything from dementia, cardiovascular disease and cancer? Unfortunately, the individuals most vulnerable to a severe COVID-19 infection, the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions, also tend to be the ones suffering the most from this increased inactivity. In individuals with some beginning balance problems, loss of muscle and bone mass or general deconditioning, the “new normal” may be the last straw, predisposing them to a detrimental loss of function. Others, while not at risk of potentially dangerous falls or loss of independent function, may be bothered by a loss of strength, unwelcome weight gain and increased aches and pains, or a worsening of already existing musculoskeletal complaints. Even our children are moving less than before, and certainly less than what is ideal. Is there anything we can do to prevent these quarantine side effects, or should we count the loss of physical fitness as yet another COVID-related loss in a world that’s changed so much? The answer, of course, is a resounding no. In March I wrote this post outlining the potential dangers of inactivity, offering a simple but reasonably comprehensive program to help readers prevent the deleterious effects of inactivity. So how are we doing, almost a year into our new reality? To their credit, most of my previously active patients have found some alternative way of staying active. However, now more than ever, variety is being sacrificed and our bodies suffer the consequences. The reason this matters is that physical activity, even as we point to it with a sweeping gesture and give it all one name, ‘exercise,’ is surprisingly specific in its effects. An online yoga class may offer an excuse to stand up and fold your body into a position different from sitting, which is great—we certainly need that variety—but it does nothing for your heart and surprisingly little for your other muscles. Perhaps you’ve bought a rowing machine or stationary bike? Good for you! Used correctly, these will offer benefits both to your cardiovascular system and even affect certain hormone levels in a beneficial way. But they will not allow you to move in a varied way, work on your balance and coordination, and strengthen your body uniformly, nor increase your stability. A good place to start is a test for musculoskeletal risk factors to find out whether you have some specific areas of weakness to be aware of. So what’s the solution? It’s tempting to first reflect on what type of movement we enjoy and go for that, but this is bound to lead to an approach to exercise that offers benefits in some areas, while leaving you lacking in others. Having good enough balance to plod through the snow is no good if you’re not strong enough to do so. You may have the stamina to pedal fast on a stationary bike, but suffer from spinal pain due to weakness in crucial muscles. A better approach is to first reflect on our goals and challenges, and then reverse-engineer from there. Here’s how that works: Let’s say you’re a 55-year old sedentary worker with some neck and low back pain. You used to enjoy a Zumba class once a week and go for walks. Now Zumba is no longer available, and when you’re done with work, which you perform seated by a computer all day, it is dark and uninviting outside, and you’ve been finding it hard to fit in some health-promoting activity in your day. To come up with the best overall solution for you, take a moment to reflect on your goals, challenges and resources, working like this: Goals: Prevent weight-gain, achieve reasonable cardiovascular fitness (which also helps protect against serious COVID-19 complications), eliminate the neck and low back pain, maintain enough strength to be functional and comfortable with everyday activities. The good old “looking good naked,” increasing your energy levels, better sleep, decreased stress levels and improved mood are all laudable goals as well! Challenges: Pain in the neck and low back, need to work on the computer during the day, preferred physical activity no longer available, feel unsure about how to go about strengthening. Resources: Financially able to purchase equipment, classes etc, motivation to feel better, able to structure the day more freely than at the office, and access to physical therapists, online classes, etc. Now you have a more clear picture of your needs, and will be better able to choose activities that will help you meet your goals! If laying it out like this doesn’t shed enough light on how to proceed, don’t overlook the benefits of discussing your situation and goals with your physical therapist and getting some solid professional advice. Problem-solving Now let’s problem-solve! Your pain probably has a lot to do with the long hours spent sitting in the same position. This weakens the stabilizing musculature of your spine and leaves the spine unprotected. Your body’s tissues don’t like being held still, in the same end-range position, and this contributes to your discomfort through decreased oxygenation of muscles and overloading of ligaments. Your heart needs for you to be a bit out of breath (often referred to as “cardio” or cardiovascular exercise) on a regular basis, and your muscles and bones need strain, or resistance training in order to not atrophy and be replaced by fat tissue. Putting all this together, the plan might look like this: Throughout the day: Vary your position often. Alternate between sitting upright and leaning against the back rest, and between sitting and standing while you work. Take breaks to vary your position. You want to reverse the position you spend most of your time in: stretch hip flexors, straighten your spine, bend it backwards, raise your arms, rotate your trunk. You’ll find the most essential stretches here. Simple! Daily: Work on your stability. When the stabilizing muscles don’t properly stabilize the small bones of your spine, fatigue, pain and gradual degenerative changes follow. Start here with a safe and effective, exercise for spinal stability. Simply sitting upright has also been shown to activate the spinal stabilization muscles throughout your spine, including your neck. Three times a week: Get your heart pumping. Go for a brisk walk, or for a run, jump rope, use machines (stationary bikes, rowing machines etc) or perform resistance training with enough weight and without breaks to leave you breathing heavily. A series of jumps is another great way to get some higher-intensity cardiovascular exercise. If you’d like to avoid the impact, whether to spare yourself or your neighbors, you can perform a brief HIIT (high-intensity interval training) body-weight training session that gives you cardiovascular exercise and strength training all in one! Three times a week: Make your muscles work. There's no need to purchase expensive, bulky equipment. Simple exercise bands offer the same resistance as weights do, and a lot of resistance training can be performed without any equipment at all. Squats, push-ups etc (see my pandemic training program for simple ideas) work very well, and should you want to add resistance you can get far with milk jugs, bags weighted down by books etc. Again, using your body weight is quite sufficient for basic strength. A common mistake people make when considering strength training is picturing yourself holding a dumbbell in your hand, moving the arm to strengthen it. The lower body muscles are actually much more important, both functionally and for your overall health, so think more about squats, stepping up and down etc. Upper body muscles are also important, but knowing how to prioritize is step number one. And remember, stabilizing exercise was listed above overall strengthening! This is important in order to avoid injury and pain, both acute and long-term. Remember, you don’t need to perform all your exercises at once. Body weight exercises are a great way to break up the physical monotony of sedentary work! Every day: Balance and coordination. There are obvious reasons why balance and coordination are important, and safety is of course the number one reason. But poor coordination of movement also contributes to poor quality of movement, and thus to degenerative changes and injuries. Balancing on one leg is a simple way to start, and it can be progressed through adding a soft surface to stand on, closing your eyes, moving your arms or the opposite leg, etc. Tuning in to your body and the sensations in it while you perform your exercises is a simple way to gradually improve your sense of position. Get used to looking up instead of at the floor when you walk and exercise - we tend to compensate for loss of proprioception through our visual sense without even realizing it! Compare what you see in the mirror when you move with how it feels with your eyes closed. And as an example of the fact that your body is a system where one part depends on its integration into the whole, the stabilizing exercises for your spine are also very important for your ability to balance! Start small Now that you have a game plan it may be tempting to make a bold move and start doing it all at once. But big, dramatic changes tend to lead to a disappointing cycle of boom and bust. Consider, instead, starting small and building on previous successes through incremental additions. For the first week, commit to postural changes, using a reminder on your phone, or a free app such as Insight Timer. Set reminders to reverse and change your position at least every 50 minutes. Once this habits starts to feel familiar, add a 5-10 minute session of the stabilizing exercise. You can add a habit of performing simple balancing exercises (eg every time you visit the bathroom). Create an association with washing your hands (after all, we’re doing that more than ever these days) and balancing on one leg. Later, challenge yourself a bit more. Start adding cardiovascular exercise to your routine, and if you are short on time, remember that the 12 minute HIIT program offers both cardiovascular training and strengthening! So, now that you are committed to a well-rounded exercises program, how will you benefit? Well, how about staying alive, for one? In a 2004 study being fit or active was associated with a greater than 50% reduction in risk of death from any cause and from cardiovascular disease. You will see a decreased risk of cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, hypertension, intermittent claudication, metabolic disorders such as diabetes, muscle, bone and joint diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, osteoporosis), osteoporosis, dementia, depression, anxiety, obesity, elevated LDL levels, frailty, and of course severe Covid-19-related illness. Your immune system benefits greatly form exercise, and the effects of exercise on our psychological well-being are so powerful that it’s been proposed that exercise may be considered as a psychoactive drug. So if you’ve been feeling a bit bummed out about the losses we’ve endured over the past year, you might want to try to add more, and varied, exercise to the mix. Your mood will improve, and over time, so will your physical health, energy and productivity. Start where you are Does all this seem like a bit too much? Does just reading the list make you feel tired? If so, consider an important rule (that I've made up :-): Start where you are! Give yourself some time to create good habits, starting with regular postural changes. When you're ready, add some simple stabilizing exercises, and before you know if, you'll feel ready to add the rest. While it’s hard to make up for the loss of social interaction, limits on travel, eating out and visiting movie theaters and museums, we can choose to make the best of the situation and, when it’s safe to do so, emerge from our long quarantine in even better physical shape than before. Rationale: The human body needs to be able to perform a variety of movements. We need these movements both to be fully functional and safe, and because they actually help maintain a healthy body. Loss of the ability to perform movements such as the ones included in the following self-test has been found to be correlated with an increased risk of musculoskeletal dysfunction and injury, both acute and gradual. Periodically assessing your risk profile and addressing deficits can help you prevent musculoskeletal injuries, poor performance and degenerative changes. Self-test procedure: Attempt to perform each test with good form, exactly as shown. If there are two versions of the test, perform the easier version first. Unable to complete the test → severe deficit, increased risk of musculoskeletal injury. Able to complete the first test → go on to the second version. Able to perform the first, but not the second test→ small to moderate deficit and risk. Able to perform second test→ optimal, no deficit, no sign of increased risk. Disclaimer: This test does not constitute diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. For diagnosis or treatment, please consult the appropriate healthcare professional. All tests and exercises are performed at your own risk. If you have any medical condition or other limitation that may put you at risk of injury while moving or performing this test, please consult the appropriate healthcare professional prior to doing so. This test may only be reproduced with the permission of the author.